No products in the cart.

10 British Female Artists You Should Know and Why Their Work Matters

British female artists have shaped how we see sculpture, painting and installation just as much as their male counterparts, yet their stories still tend to sit slightly off to the side of the main narrative. Walk into a museum, and their names often appear on wall labels you recognise once you see them, rather than names that come to mind instantly.

This guide introduces ten British women artists whose work is central to understanding modern and contemporary art in the UK. They cover a wide range of practices, from carved abstract sculpture to film, performance based work and politically charged installation. None of them are included in the existing Town Quay Studios blog on British female artists, so you can treat this as a companion piece that opens up a different set of voices.

For each artist, you will find a short background, key themes, at least one important work and a practical suggestion for how to look. The aim is not just to list names, but to give you a way into the work that feels usable next time you are in a gallery or browsing an online collection.

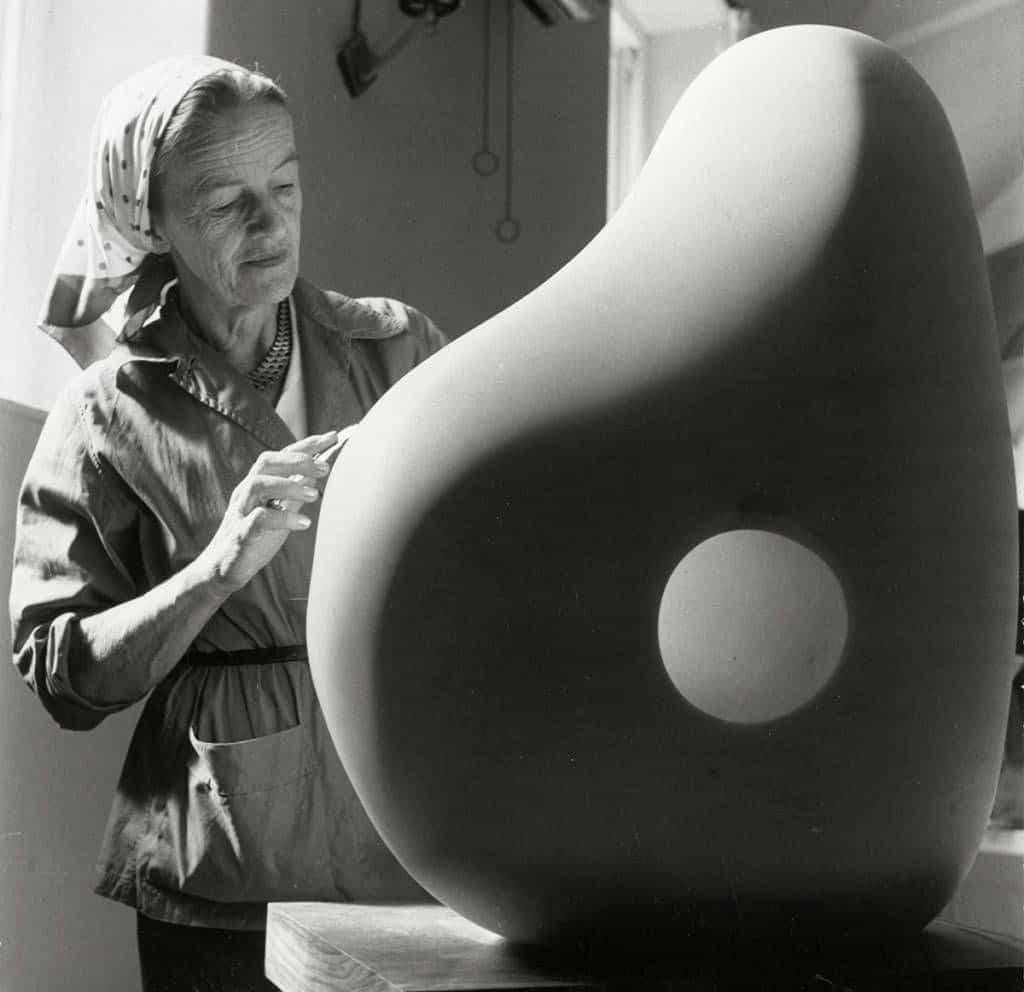

1. Barbara Hepworth

Carving space, light and landscape

Barbara Hepworth, born in Wakefield in 1903, is one of the most influential British sculptors of the twentieth century. She is closely associated with St Ives in Cornwall, where the coastal landscape and changing light fed directly into her carved and cast forms.

Hepworth is known for abstract sculptures that balance solid mass with carefully pierced holes and taut strings. Works such as Pelagos, Winged Figure and Sculpture with Colour (Oval Form) Pale Blue and Red combine smooth curves, hollowed interiors and lines of string that seem to draw invisible forces across the form. Those strings are not decorative details; they behave almost like drawn lines in space, turning air into part of the sculpture.

A helpful way to look at Hepworth’s work is to move slowly around it and watch how the holes frame what is behind them. In a gallery, that might be another artwork or a window. Outdoors, it might be a patch of sky or a corner of building. Hepworth was very aware that her sculptures would not be seen from a single fixed viewpoint. The shifting relationship between object and surroundings is part of the work itself.

Hepworth matters for British female artists because she carved out a serious, international career at a time when women sculptors were still treated with suspicion. Recent exhibitions of her stringed works, including pieces that had been in private collections for decades, show just how experimental she was with materials and engineering, not just with form.

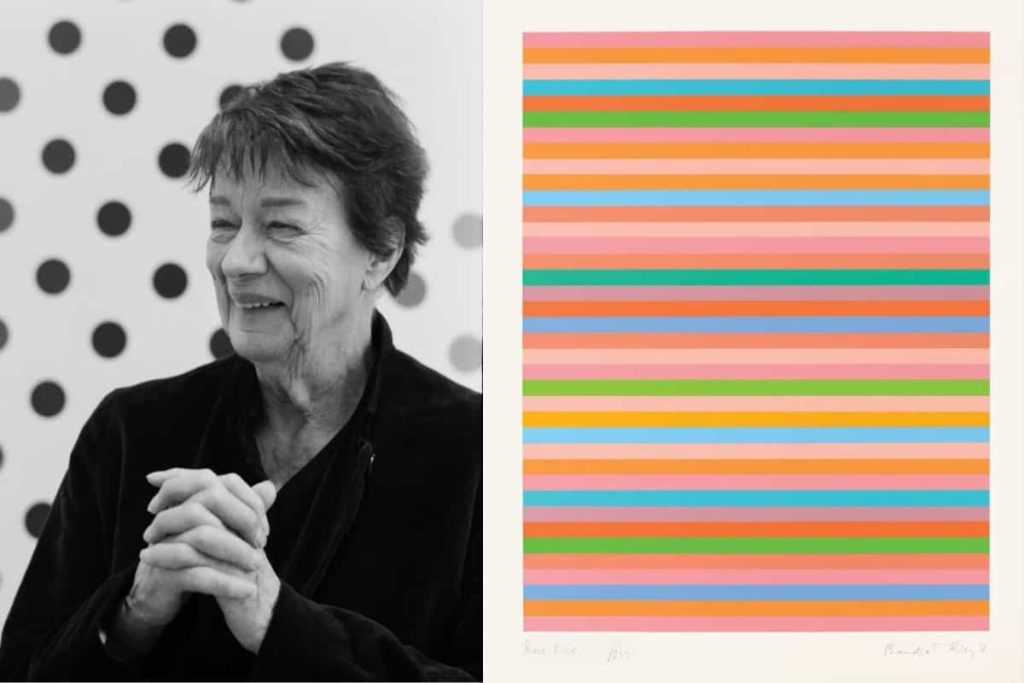

2. Bridget Riley

Painting as pure perception

Bridget Riley, born in London in 1931, is one of the leading British women painters of the past sixty years. Often associated with Op art, her work explores how carefully arranged lines, stripes, curves and colours affect the eye and the body.

Her early black and white paintings such as Movement in Squares and Fall use repeated shapes to create optical effects that feel almost physical. The surface of the canvas is flat, but the pattern makes it appear to bend, swell or recede. Later, Riley moved into complex colour relationships, building sequences of stripes and diagonals that seem to shimmer as you move past them.

A niche way to experience Riley’s work is to pay attention to your peripheral vision. Instead of staring only at the centre of a painting, stand at an angle and let it sit just off to one side of your view. Small shifts in your posture will change how the pattern behaves. People sometimes describe her paintings as exhausting, but that sense of effort is part of the point; Riley is inviting you to notice perception as an active process, not a passive one.

For British women artists, Riley’s importance is twofold. She proved that a woman could sit at the centre of a highly technical, abstract field, and she also demonstrated that rigorous planning and emotional impact can sit together in the same work. Her influence can be traced in many younger painters who use pattern and colour as a way of thinking about attention, rhythm and time.

3. Maggi Hambling

Sea, sculpture and unapologetic emotion

Maggi Hambling, born in Suffolk in 1945, is a painter and sculptor whose work moves between fierce sea paintings, intimate portraits and controversial public sculpture. She is well known for her North Sea series, large paintings of waves that she has been making since the early 2000s, returning again and again to the same stretch of coast.

In these works the sea is never simply a backdrop. Thick, dragged brushstrokes and splashes of paint record movement and collapse. Hambling has spoken about drawing the waves on winter mornings until she felt she knew their behaviour from the inside. That combination of close observation and expressive handling gives the paintings a particular tension; they are neither romantic views nor purely abstract surfaces, but something between.

Hambling’s public sculptures often stir debate. Scallop, her stainless steel shell on the beach at Aldeburgh made as a tribute to Benjamin Britten, is a good example. Some locals initially found it intrusive, while others embraced it as a landmark that changes with the weather and tide. One useful way to approach Scallop is to sit inside the curve of the metal and listen to how it frames the sound of the sea. The work is as much about hearing as about looking.

Hambling’s role in the story of British female artists is as a maverick who has insisted on emotional directness. She treats painting and sculpture as ways to address subjects like death, queerness and memory without softening them. Even late in her career, after health scares and the loss of a finger in an accident, she continues to work daily, adjusting her methods instead of slowing down.

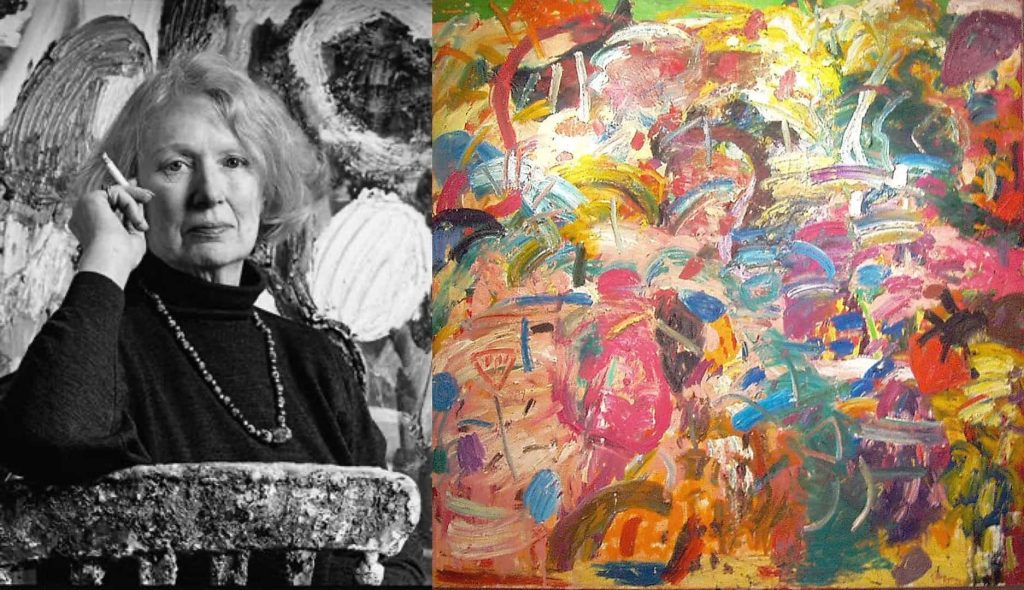

4. Gillian Ayres

Colour as physical force

Gillian Ayres, born in 1930 and active until her death in 2018, is one of Britain’s most important abstract painters. Her canvases are full of saturated colour and energetic mark making. They feel less like paintings of something and more like records of immersion in paint itself.

Ayres started out working with a slightly more muted palette, but by the late 1950s and early 1960s she was already pushing paint into thick, layered surfaces in works such as Distillation and Break off. These paintings show how she built up clusters of marks and colours that just about hold together, like a chord in music that is on the edge of dissonance. Later in her career, the shapes became larger and more defined, but the sense of abundance remained.

A useful way to look at Ayres’ paintings is to scan for the least obvious colours. Among the bright oranges and pinks, there are usually odd greys, sour greens or muddy browns woven into the surface. Those quieter notes are what stop the painting from becoming decorative. Once you see how they work, it becomes easier to understand the structure underneath the apparent chaos.

Ayres matters in the context of British women artists because she claimed large scale, energetic abstraction as a field where women could work with complete seriousness. She continued to paint ambitiously into later life, often living and working in rural settings rather than in the centre of London, which gave her practice a slightly independent track away from the fashions of the moment.

5. Phyllida Barlow

Sculpture that sprawls, leans and crowds

Phyllida Barlow, born in 1944 and sadly lost in 2023, spent decades teaching and making sculpture before gaining wider recognition later in her life. Her installations use ordinary materials such as timber, cardboard, concrete, fabric and paint to build sprawling structures that feel both playful and precarious.

What stands out in Barlow’s work is the way it takes over a space. Rather than placing a few tidy objects on plinths, she often filled entire galleries with columns, bundles, barriers and tangle. Her Tate Britain commission and later exhibitions at the Royal Academy surrounded viewers with colour and bulk. You have to navigate around, under or between the works, which makes you constantly aware of your own movement and scale.

An interesting detail is how often her sculptures show signs of construction rather than hiding them. Splashes of paint, visible screws, rough edges and sagging elements are left on display. That is a deliberate refusal of perfection. Barlow treated sculpture as a kind of thinking with materials, where traces of trial and error are part of the final work.

For British female artists, Barlow’s importance lies partly in her long teaching career. She influenced generations of students through art schools as well as through her own exhibitions. Her late recognition, including representing Britain at the Venice Biennale, is also a reminder that serious careers in sculpture do not always follow a neat early success model.

6. Cornelia Parker

Transforming everyday objects through destruction

Cornelia Parker, born in 1956, is a British artist whose installations often begin with acts of destruction. She works with garden sheds, silverware, chunks of soil, even a full length cast of a cartoon character, and subjects them to processes such as steamrolling, exploding or stretching, before reassembling the fragments in precise ways.

Her best known work, Cold Dark Matter: An Exploded View, started as an ordinary shed filled with domestic clutter. Parker had the army blow it up, then suspended the charred pieces around a single lightbulb, freezing the moment of explosion in mid air. The result is strangely calm. As you walk around it, the fragments create shifting constellations of shadow on the gallery walls.

A niche way to approach Parker’s work is to look for the original function of each object and then notice how that function has been interrupted. In Thirty Pieces of Silver, flattened spoons and teapots hover slightly above the floor in circular groupings. In Magna Carta, embroidered panels recreate a long online document. The works often function like diagrams of social and political systems, built from familiar things that have been pushed into new roles.

Parker’s place among British female artists is significant because she uses large scale installation and ambitious collaborations without losing a sense of wit. Her practice demonstrates that conceptual work can be grounded in very tangible, recognisable materials, which helps audiences connect even when the ideas are complex.

7. Lynette Yiadom Boakye

Imagined portraits and the time of looking

Lynette Yiadom Boakye, born in London in 1977 and of Ghanaian heritage, is widely recognised for her paintings of Black figures who are not direct portraits of real people. Instead they are imagined subjects, built from memory, fragments of photos and the artist’s own painterly decisions.

The people in her paintings sit, stand or recline against fairly simple backgrounds. Their clothes, gestures and expressions feel contemporary and at the same time slightly outside of time. Titles such as Fly In League With The Night or Ever the Women Watchful add a poetic layer without telling you exactly what to think. That openness is deliberate; Yiadom Boakye has said that the works are not illustrations of stories, but invite viewers to bring their own.

One useful way to look at these paintings is to give yourself more time than you might usually spend in front of a single work. Because the surface handling is subtle rather than flashy, details emerge slowly: the way a hand is painted with just a few strokes, or how a patterned sock echoes a mark in the background. It can be helpful to step back, read the title, then step forward again and see if your reading of the figure has changed.

Yiadom Boakye matters to British female artists because she has created a body of work that centres Black subjects without reducing them to symbols. Her large survey exhibition Fly In League With The Night at Tate Britain and other museums confirmed that it is possible to place imagined Black lives at the heart of European painting traditions and to do so on her own terms.

8. Veronica Ryan

Seeds, memory and the politics of care

Veronica Ryan was born in Montserrat in 1956 and moved to the UK as a child. Her sculptures and installations often use forms such as seeds, pods, fruit, cushions and containers to explore themes of migration, memory and the labour of care.

Ryan gained major public attention with her Hackney Windrush commission, a group of enlarged cast forms based on Caribbean fruits installed in east London. The work quietly honours the Windrush generation and their ongoing presence in British life. In the studio, she often works with nets, stitched materials and stacked containers, building arrangements that feel both fragile and resilient.

A niche insight when spending time with Ryan’s work is to notice how much of it is about holding, storing and sheltering. Nets may be empty or full. Containers may be closed or open. That play between protection and exposure maps quite closely onto experiences of migration and family life. The sculptures rarely lecture; instead they offer a physical vocabulary for feelings that are usually discussed in words.

Ryan’s Turner Prize win in 2022, at the age of 66, underlined how important her long, steady practice has been. For British female artists, especially those from diasporic backgrounds, her recognition is a sign that quiet, materially attentive work can carry as much weight as loud, spectacular gestures.

9. Tacita Dean

Time, film and drawing with simple tools

Tacita Dean, born in 1965, is a British artist known for her use of analogue film, photography, drawing and sound. Her works often focus on a single place, object or person over time, attending closely to small shifts in light, weather or gesture.

Dean has made films about subjects as varied as a ship being broken down, a Berlin television tower, the artist Cy Twombly and natural phenomena such as sunsets and avalanches. She also creates large chalk drawings on blackboard, where the slightly dusty, erasable surface becomes part of the meaning. Recent exhibitions such as Blind Folly in the United States have brought together film, drawing and overpainted photographs to show how she works across mediums.

A helpful way to watch Dean’s films is to accept that not much may happen in the conventional sense. Instead of action, you get duration. A tree, a cloud, a building or a face holds your attention for longer than film usually allows. As a viewer, you become aware of your own restlessness or patience. That self awareness is one of the quiet achievements of her work.

Dean’s place in the story of British female artists comes from her insistence on analogue processes at a time when digital media dominates. She has argued passionately for the continuing value of celluloid film and has collaborated with institutions to keep it available. For younger artists, she demonstrates that you can build an international career by staying loyal to a particular way of working while still experimenting within it.

10. Mona Hatoum

Domestic objects, maps and quiet threat

Mona Hatoum was born in Beirut in 1952 to Palestinian parents and settled in London in the mid 1970s. She is widely regarded as a British based artist, even as her work continually reflects on exile, displacement and political conflict. Her installations, sculptures and works on paper often use familiar domestic objects and maps, but in ways that disturb their usual sense of safety.

Hatoum has, for example, enlarged a kitchen grater to the scale of a room divider, turned baby cots into cages, and laid out the world map in fragile glass marbles that scatter if disturbed. She often uses materials such as steel, barbed wire and glass that conjure both minimalism and militarised borders. The works are visually clear but emotionally complicated, sitting somewhere between sculpture and social metaphor.

A small but useful trick when looking at Hatoum’s work is to ask yourself where your body would be in relation to the object if it were used in daily life. Would you sit at it, hold it, walk across it. In the gallery, that expected relationship is usually blocked. The work might be too sharp, too unstable or too precious to touch. That gap between habitual use and present impossibility is where much of the tension lives.

Hatoum matters for British female artists because she shows how personal and political histories can be embedded in objects without resorting to slogans. Her practice has influenced many younger artists who work with domestic materials and global themes, especially those dealing with migration and geography.

Why these British female artists deserve space in your memory

Taken together, these ten British female artists give a sense of how wide the field really is. Some, like Barbara Hepworth and Gillian Ayres, are firmly part of modern art history. Others, such as Veronica Ryan and Lynette Yiadom Boakye, are reshaping what British art looks like right now. Between them you find carving, casting, painting, filming, exploding, stitching and casting fruit in bronze.

A pattern emerges if you look across their practices. Many of them work with the push and pull between solidity and fragility, whether it is Hepworth’s pierced forms, Hambling’s waves that almost fall apart into marks, Barlow’s leaning structures, Parker’s exploded shed or Ryan’s nets and pods. Others focus on time and perception, like Riley’s optical rhythms and Dean’s long films. Some take the domestic and make it unsettling, as Hatoum does.

For someone exploring British female artists, the most useful step is often very simple. When you next visit a museum or open a gallery website, make a point of seeking out one work by a woman you do not already know and spend longer with it than you normally would. Not as a duty, but as an experiment in attention. Over time, those individual encounters build into a more complete, and more interesting, picture of what British art really looks like.

Leave a Reply