No products in the cart.

Art and Mindfulness: How Creative Practice Can Improve Mental Health

Art and mindfulness meet in a very practical place. Both invite attention to the present moment, help with expressing emotions that can feel difficult to put into words, and offer a safe space to settle the nervous system. When people talk about improved mental health, they often picture a formal meditation practice. In reality, creative practice can be just as grounding. Creating art, playing an instrument, or simply pausing to look closely at a painting are all gentle ways of engaging in creative activities that fit into daily life.

Mindfulness practice is the habit of noticing what is happening right now without judgement. Incorporating art into that habit turns attention into action. Colour mixing, mark making and rhythm give the mind something steady to rest on. That steadiness supports stress management because it draws focus away from worry loops and back to simple sensations such as breath, touch and sound. For many people, this becomes an outlet for emotions, especially when talking feels hard.

This approach does not ask anyone to be “good at art”. It asks for a few minutes of honest noticing. A pencil line, a collage scrap, a repeated chord, or a quiet look at a familiar artwork can train attention and build problem solving skills in small, repeatable ways. Over time, engaging in creative activities can become a reliable part of self care alongside movement, sleep and social connection. For some, these moments may help the body settle, which is one reason researchers study outcomes such as cortisol levels, mood and anxiety in relation to creative activity.

This article keeps the focus practical, not medical. It shares ideas that anyone can try at home or on a gallery visit, with examples drawn from well known artworks and simple exercises. It also makes a clear distinction between everyday creative expression and art therapy, which is a professional, clinical service for specific health conditions. Readers will find short prompts that can be used with paintings, drawings, textiles and music, plus a simple seven day plan to help mindful creativity become part of daily life.

Why pair art with mindfulness

Art and mindfulness sit well together because both invite attention to the present moment. When a person is creating art or quietly looking at a painting, the mind has a clear focus. Colour, line and rhythm become anchors that make it easier to notice breath, posture and small sensations. This kind of mindful creative practice supports stress management in daily life and gives people a safe space for expressing emotions without pressure to find the right words.

Mindfulness practice is often introduced through a seated meditation practice, yet many people find it easier to start by engaging in creative activities. A short drawing, a few bars on a piano, or a simple collage can shift attention from racing thoughts to steady, repeatable actions. That shift helps regulate mood and can support improved mental health without becoming overly clinical. Researchers sometimes study markers such as cortisol levels and self reported wellbeing, but the day to day value is simpler. Creative activity makes it easier to return to the present moment and reset.

Pairing art with mindfulness also builds useful problem solving skills. In creative work, there is always a small decision to make. Which shape comes next. How dark should this tone be. Where does a rhythm begin and end. These decisions are low stakes and playful, which helps people practise flexible thinking and patience. The process becomes an outlet for emotions as well as a gentle workout for attention. It is not about being perfect. It is about noticing, adjusting and trying again.

Quiet viewing can be just as powerful as making. Slow looking gives the eyes and breath a shared pace. Many galleries now offer short prompts that encourage this style of attention. A five minute meditation with a single artwork can reduce mental noise and set a calmer tone for the rest of the day. If someone prefers sound, playing an instrument or humming a steady note offers the same kind of focus and can sit comfortably alongside a light meditation practice.

It is also worth naming the difference between self guided creative expression and art therapy. Creative practice at home or in a gallery is personal and flexible. Art therapy is delivered by trained professionals and usually relates to specific health conditions or goals. Keeping this distinction clear allows people to enjoy the benefits of incorporating art into daily life, while knowing where to look if they want structured clinical support in the future.

The science in brief

Researchers have been looking at how engaging in creative activities relates to improved mental health. Reviews of the evidence suggest that creating art, playing an instrument and other forms of creative expression can support stress management, mood and social connection by drawing attention to the present moment. The benefits are usually modest, but they are consistent across ages and skill levels, which is why many people choose to incorporate art into daily life alongside movement, sleep and talking therapies.

Read : What is the evidence on the role of the arts in improving health and well-being? A scoping review

One often cited experiment found that a single forty five minute session of creating art was associated with lower cortisol levels in adults, regardless of prior art experience. Participants described the session as a safe space and an outlet for emotions. This does not make art a medical treatment in itself. It does show how a short, focused creative activity can help the body and mind settle after a busy day.

There is also growing interest in music and group arts. Singing, drumming and simple rhythm practices can act like a light meditation practice because they steady breath and attention. International public health bodies now track the role of the arts in wellbeing, with summaries that point to benefits for anxiety, social isolation and quality of life, while reminding readers that results vary and that creative practice complements, rather than replaces, clinical care.

It helps to keep a clear line between everyday creative practice and art therapy. Art therapy is a professional service delivered by trained therapists for specific health conditions and goals. Self guided drawing, collage or mindful viewing can sit alongside that, offering gentle ways of expressing emotions and practising attention without becoming clinical.

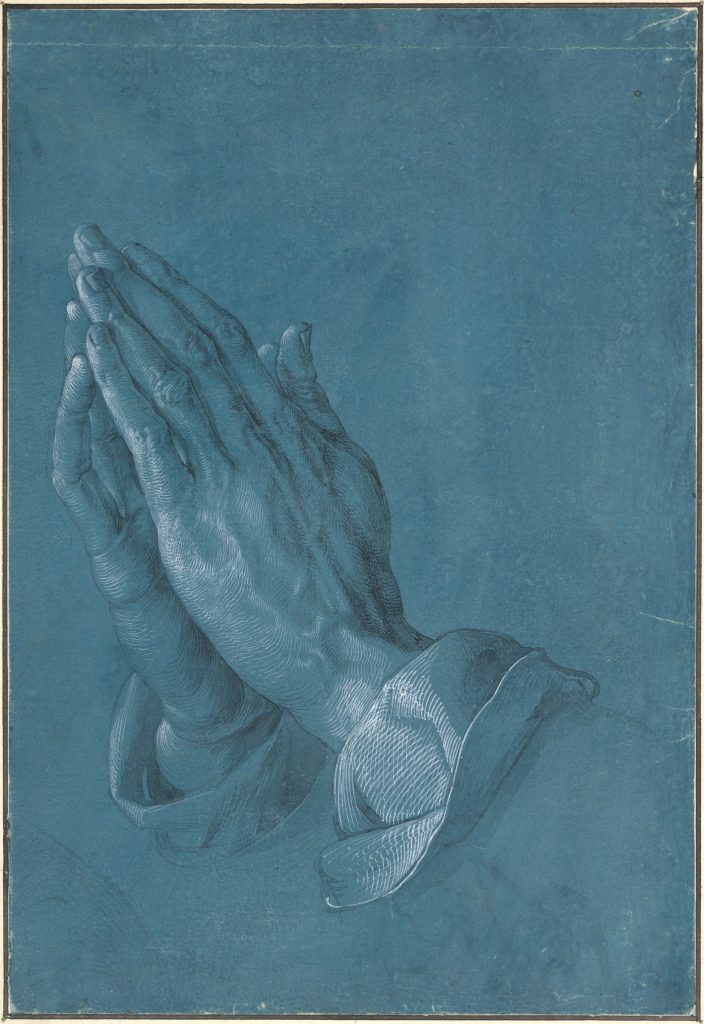

Mindful viewing, with artworks you can visit or view online

Mindful viewing is a simple way to combine art and mindfulness in daily life. Slow looking gives attention a clear anchor in the present moment. Colour, light and rhythm become steady guides, which can support stress management and offer a safe space for expressing emotions without needing to explain anything out loud. The pieces below work well as prompts for creative expression. Each comes with a short cue you can try on a gallery visit or at home on a screen. This is not art therapy. It is everyday creative practice that can sit alongside a light meditation practice or other engaging in creative activities.

Mark Rothko, Seagram Murals, Tate

Rothko’s deep colour fields reward quiet, sustained attention. Let the surface fill your view and notice how your breath settles as your eyes rest on one panel, then another. This steady looking can become an outlet for emotions and a gentle reset when the day feels busy. Read more

Mindful cue

Rest your gaze on one panel for three slow breaths. Notice edges, afterimages and the rise and fall of your chest.

Agnes Martin, grid paintings, Tate

Martin’s fine lines and soft washes encourage calm, precise attention. The repeated structure helps train focus and patience, which in turn supports problem solving skills in other parts of life. The restraint of the surface leaves room for expressing emotions in a quiet way.

Mindful cue

Trace one pencil line with your eyes as you breathe in, then the next line as you breathe out. Continue for one minute.

J M W Turner, Rain, Steam, and Speed, National Gallery

This painting is alive with movement, weather and light. Spotting small details can bring attention back to the present moment and help thoughts slow down. Many visitors find that this kind of slow looking feels like a brief meditation practice in a public space.

Mindful cue

Name five details you had not noticed, then soften your shoulders and jaw before looking again.

Claude Monet, Water Lilies, National Gallery

Monet’s surface surrounds the eye with shifting colour and almost no horizon. That lack of fixed depth invites breath to set the rhythm. Watching brush marks while counting breaths can be a useful way to regulate attention on tired days.

Mindful cue

Match your breath to the visible brush marks for one minute. If your mind wanders, return to a single leaf shape and begin again.

Bridget Riley, optical paintings, Tate

Riley’s patterns appear to vibrate and flow. The sensation asks for careful noticing and a steady body position. Anchoring awareness in the soles of the feet while looking can reduce the sense of visual tilt and build tolerance for lively visual information in a safe space.

Mindful cue

Notice the feeling of movement in the image, then bring attention down to your feet on the floor and count three slow breaths.

Katsushika Hokusai, The Great Wave, British Museum

The rise and fall of the wave is an easy breath guide. Pairing inhalation with the lift of the wave and exhalation with the curl gives a clear rhythm that fits short pauses in daily life. This is a good option for people who like a crisp image to focus on.

Mindful cue

Inhale on the lift, exhale on the curl. Repeat for six cycles, then notice the small boats and the shape of Mount Fuji.

Winifred Nicholson, still life and light, Kettle’s Yard

Nicholson’s paintings of flowers, windows and light are small lessons in noticing. The hush of her colour choices supports gentle creative expression and a sense of quiet order. They are ideal when someone wants a moment of attention that does not feel heavy or clinical.

Mindful cue

Name three colours in the painting, then notice the light between them. Let the breath follow the slow changes in tone.

Eric Ravilious, drawings and watercolours, Towner Eastbourne

Ravilious often used clear lines and carefully balanced tones. Following a single contour with the eyes is a simple way to practise present moment focus. The clarity of form also makes it easier to sketch for a minute or two, which turns viewing into creating art.

Mindful cue

Pick one contour and follow it with a single slow breath. Choose a second contour and repeat. If you like, copy the shape in a tiny thumbnail sketch.

If you prefer sound, the same approach works with music. Playing an instrument or humming a steady note can be paired with looking at an artwork for a few breaths, which ties visual and auditory focus together. That way of incorporating art into mindfulness builds a simple habit that supports improved mental health without feeling rigid or medical.

Creative expression as a safe space

Creative expression gives people a reliable way to stay with the present moment without forcing anything. When someone is creating art or looking closely at an image, attention has a simple task. The hand follows a line. The eye explores colour. Breath matches a rhythm. This is a calm setting for expressing emotions that might be harder to speak about. It is also a practical form of stress management that sits well alongside movement, sleep and a light meditation practice. Read more here

Many people describe making or viewing art as an outlet for emotions. The materials act as a container. Charcoal can hold frustration. Watercolour can carry a mood that does not yet have words. This is one reason creative practice fits neatly into daily life. Five minutes of mark making after work or a short sketch on a lunch break can leave the mind steadier and the body a little softer. Some studies track changes in cortisol levels after short sessions of drawing or collage, but the important point for day to day use is that the activity feels safe, absorbent and repeatable. read Reduction of Cortisol Levels and Participants’ Responses Following Art Making

A self guided session cannot diagnose or treat health conditions. What it can do is offer small, consistent moments of agency. Each choice is manageable. Which pencil. Which patch of colour. Where to place the next line. Those micro decisions build problem solving skills that carry back into work and relationships. The effect is modest and cumulative. Attention learns to return. The nervous system practises moving from scattered to settled. Over weeks, this can support improved mental health without turning creative activity into something clinical.

It helps to understand how this differs from art therapy. Art therapy is delivered by trained professionals who use creative processes within a therapeutic relationship. It may be offered for specific needs and goals. Self guided drawing, collage or mindful viewing is personal and flexible. Both approaches can be valuable, yet they are not the same. Keeping the distinction clear lets people enjoy incorporating art into daily life while knowing where to find structured support if they want it.

A short practical sequence helps this feel less abstract. Choose a simple material such as a soft pencil and a scrap of paper. Set a timer for three minutes. Track your breath for the first ten seconds. Then begin creating art with one continuous line, moving as slowly as your breath. If feelings swell, pause and notice feet on the floor, then continue. When the timer ends, add three areas of light shading. This tiny practice blends mindfulness practice with creative activity. It creates a safe space, offers an outlet for emotions and gives attention a quiet place to rest. Read NHS Self-help

Everyday mindful creativity in daily life

Mindful creativity works best when it fits the shape of daily life. Short, regular moments of attention are more helpful than rare, long sessions. The aim is to give the mind and body a safe space to return to the present moment, support stress management, and offer a steady outlet for emotions. You do not need special materials. You do not need to be good at drawing or music. You need a few minutes and a kind attitude to yourself.

Creating art

A pencil, a biro, a bit of scrap paper. That is enough to begin. Creating art is a practical way to anchor attention and to practise noticing without judgement. The small decisions involved build problem solving skills that carry into work and relationships. As with any mindfulness practice, it is fine if the mind wanders. Each time you notice, bring attention back to breath and the task in hand.

Micro exercises for drawing and colour

One line, three minutes

Set a timer for three minutes. Place your pen on the page and draw one continuous line without lifting the tip. Move slowly enough that you can match the pace to your breathing. When thoughts pull you away, name three shapes you can see in the line and continue.

Tiny blocks of colour

Pick three colours from objects around you and make small swatches, no larger than postage stamps. Notice the pressure of the brush or pencil, the sound it makes, and the change in your breathing. If feelings swell, pause and notice your feet on the floor, then resume.

Contour and texture

Choose a simple object such as a mug or a leaf. Trace its outline with your eyes first, then draw that contour without looking at the page. Add two textures inside the outline. Paying attention to small textures helps return focus to the present moment and can serve as an outlet for emotions.

Playing an instrument or singing

Sound and rhythm are powerful anchors. Playing an instrument, humming, or using simple body percussion offers a clear structure for attention and breath. Many people find that two or three minutes of steady rhythm functions like a light meditation practice. It can be especially helpful for those who prefer moving or vocal tasks over quiet sitting.

Micro exercises for rhythm and voice

Four four breathing with a steady note

Sit or stand comfortably. Hum a gentle note for the length of an out breath. Breathe in for a count of four, out for a count of four, and repeat for two minutes. If your mind wanders, return to the sensation in your chest and throat.

Hand drum or tabletop pattern

Tap right, left, both, rest. Repeat this simple cycle while counting quietly. Notice how your shoulders and jaw soften as the pattern takes hold. If you prefer, clap or tap on your knees. The aim is not performance. It is attention and steadiness.

One song, mindful phrasing

Choose a familiar song. Sing one verse at an easy volume, feeling how the breath shapes each phrase. Between verses, place a hand on your diaphragm and take two quiet breaths. This is a gentle practice for stress management that fits into daily life.

Mindful making

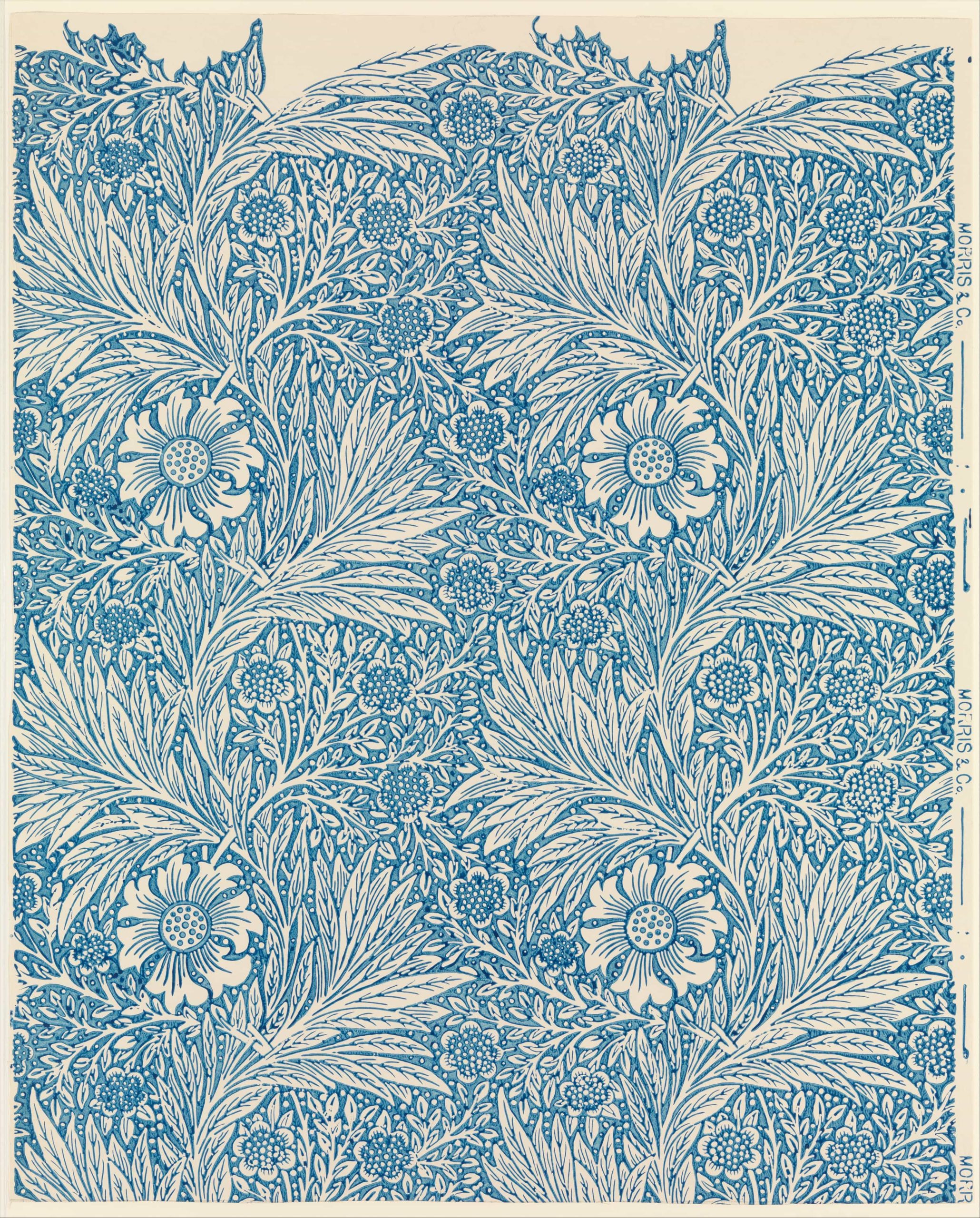

Hands on materials encourage calm focus. Collage, clay and textiles combine small movements with simple choices, which can make them ideal for engaging in creative activities after a busy day. The point is not to produce a finished artwork, but to give attention a task and emotions a container. This kind of making can complement support for health conditions without turning creative practice into art therapy.

Micro exercises for collage, clay and thread

Two shapes and a gap

Cut or tear two simple shapes from scrap paper. Glue them on a page with a small gap between them. Spend one minute looking at the space in between. Add a third shape to change the space. Naming and shaping the gap is a neat way to practise present moment focus.

Pinch pot in three rounds

With a walnut sized piece of air dry clay, make a pinch pot in three short rounds. Round one forms the basic bowl. Round two smooths the rim. Round three adds a thumb texture around the outside. Feel the pressure of your fingers and the temperature of the clay.

Thread ladder

Thread a needle and stitch a short ladder of five bars on a scrap of fabric or paper. Breathe in as the needle rises, breathe out as it returns. The simple up and down motion can become a safe space for expressing emotions that feel difficult to name.

A note on expectations

These practices are not a replacement for clinical care. They are everyday ways of incorporating art into life that can support improved mental health for many people. If you live with specific health conditions, adjust the exercises to suit your energy and access needs. Some days you may notice a calm shift. Other days you may simply complete the exercise. Both are valuable. If you ever feel overwhelmed, pause, notice your feet on the floor, and return to a few slow breaths. If you want structured support, an art therapy professional can help you work with creative processes in a clinical setting.

From creativity to community

Creative practice often begins alone, then grows richer in company. Making or viewing art with others adds a sense of belonging, gentle accountability and a rhythm that fits daily life. Shared attention to colour, sound or line gives everyone the same present moment focus, which can support stress management and create a safe space for expressing emotions in a social setting. The result is not only personal calm, but also small connections that support improved mental health over time.

Community programmes sometimes appear through social prescribing in the UK. This approach links people to groups and activities where creative expression is part of the week, from choirs to museum sketch clubs. It is designed to meet practical, social and emotional needs, and it sits alongside usual healthcare without replacing it. NHS England

Researchers and economists have begun to put numbers to the wider benefits of cultural engagement. One recent analysis linked regular participation in culture and heritage to health and productivity gains valued at around eight billion pounds a year in the UK. These estimates are not prescriptions. They simply reflect how engaging in creative activities can add up at population scale when more people feel well enough to work, care and participate.

Independent reviews also point to community level gains. Targeted museum programmes that include volunteering or social prescribing have shown improvements in subjective and mental wellbeing, especially when activities connect to local heritage and help people form relationships. Evidence is still developing, and long term studies are hard to run, but the short term picture is encouraging for both individuals and places. whatworkswellbeing.org+1

Group music is a good example. Singing together can steady breath, build confidence and create friendships. Reviews of community music suggest benefits for morale and mood in older adults, and ongoing projects continue to test similar effects for new parents and other groups. What matters for day to day life is the shared rhythm and the welcome at the door. PMCThe Guardian

Nature based creative groups can help too. Some social prescribing schemes blend arts with green spaces, such as sketching in parks, creative walking, or outdoor choirs. These activities combine mindful attention with light movement and a supportive group, which many people find easier to keep going than solitary practice. NHS England

If you are curious about joining in, look for low pressure options that suit your energy and interests. Galleries often host slow looking or drawing hours. Libraries and community centres list free or low cost groups for collage, textiles and singing. The aim is not performance. It is a regular slot where creative expression feels welcome, small decisions build problem solving skills, and attention can return to the present moment in good company.

For examples of what this looks like around the country, browse case studies from national bodies that fund or evaluate creative health programmes. These snapshots show how incorporating art into community settings can support wellbeing without becoming clinical. Arts Council England+1Creative Health Stories

Getting started

A gentle plan helps mindful creativity become part of daily life. The aim is not perfection. It is a few minutes of attention, a safe space for expressing emotions, and a steady return to the present moment. The plan below blends mindfulness practice with creative activity, using simple materials. Adjust timings to suit your energy or any health conditions. If at any point you feel overwhelmed, pause, notice your feet on the floor, and take three slow breaths.

Day one

Mindful mark making

Set a timer for five minutes. Sit comfortably and track your breath for three slow cycles. Begin creating art with a soft pencil. Draw a single, continuous line. Move slowly enough that the pace of the line matches your breathing. When the mind wanders, name a shape in the line and return to breath. This is a simple outlet for emotions and a way to practise attention without pressure.

Day two

Colour blocks from everyday objects

Choose three colours from items on your table. Paint or shade small blocks, no larger than stamps. Notice pressure, sound and the change in your breathing. Colour choices train problem solving skills in a low stakes way. If strong feelings arise, gently place your hand on your chest and lengthen the out breath.

Day three

Mindful viewing with one artwork

Open a high quality image from a trusted museum or visit a gallery. Spend three minutes in quiet looking. Let the surface fill your view, then notice your breath. If attention drifts, pick one small detail and begin again. This turns looking into a light meditation practice.

Day four

Rhythm for attention

Play a single note on an instrument or hum gently. Breathe in for a count of four and out for a count of four while sustaining the note. Repeat for two minutes. If you prefer percussion, tap a simple right, left, both, rest pattern. Sound gives breath a structure and can support stress management on busy days.

Day five

Contour and texture walk

Take a short walk and pause to draw the contour of a tree, building or cup in a café. Do not look at the page while drawing. Add two textures with light marks. This builds present moment focus, helps with expressing emotions through movement, and brings creative practice into daily life.

Day six

Hands on making

Use scrap paper for a minimal collage. Tear two shapes and arrange them with a small gap between. Look at the space for thirty seconds, then add a third shape to change the mood. Hands on choices often feel calming and can act as a safe space for feelings.

Day seven

Choose and repeat

Pick your favourite practice from the week. Spend ten minutes with it. Notice what helped. Jot two notes about when you might use this in future, for example before a meeting, after study, or to reset bedtime. Over time, engaging in creative activities like these can support improved mental health in a modest, sustainable way.

When to seek support

Self guided creative expression is not a replacement for clinical care. If low mood, anxiety or other symptoms are persistent or disruptive, consider talking therapies through the NHS. You can refer yourself in most areas. Art therapy is a clinical service delivered by trained professionals and may be suitable for specific needs. If you are in crisis, seek help now using the services below.

NHS Talking Therapies

Explains options and how to refer yourself for free psychological therapies in England.

NHS overview of talking therapies and urgent help

General information with a link to crisis support.

Urgent help for mental health

How to contact your local urgent mental health helpline.

Samaritans

Free, confidential support, 24 hours a day in the UK and ROI. Call 116 123.

Find an art therapist

Directory from the British Association of Art Therapists.

Note for readers outside the UK

Check national services in your country. In the United States, the 988 Lifeline offers phone, text and chat support.

FAQs

Is art therapy the same as self guided creative practice

No. Art therapy is a professional, clinical service delivered by trained art therapists. Self guided practice includes drawing, collage, textiles, slow looking and rhythm exercises you do yourself. Both use creative expression, but art therapy involves a therapeutic relationship and agreed goals. read more

Do I need to be good at art to benefit

No. The point is attention, breath and small choices, not performance. Studies and reviews focus on the act of making or mindful viewing rather than artistic quality. If you enjoy the process, you are already doing the useful part. read more

Can mindful creativity help with sleep and anxiety

Gentle practices can help the body settle before bed and can lower arousal during the day. People often use drawing, colour swatches or a short rhythm to step out of worry loops. If anxiety or insomnia are persistent, seek clinical support alongside creative habits. read more

Is music as effective as drawing

It depends on preference. Playing an instrument, humming or simple drumming offers a clear breath rhythm and body focus. Drawing offers visual anchors and fine motor actions. Choose the one you enjoy, or combine them. read more

What if I feel overwhelmed while creating

Stop, notice your feet on the floor, and take three slow breaths. Switch to a simpler task such as shading a small block of colour or tracing a single contour with the eyes only. If difficult feelings persist, speak to someone you trust and consider professional support. read more

References and further reading

NHS Every Mind Matters overview of mindfulness

Mind guide to arts and creative therapies

WHO Health Evidence Network synthesis report on arts and health

National Gallery five minute meditation with Turner

British Association of Art Therapists

Leave a Reply