No products in the cart.

Contemporary British Sculpture: The Artists Shaping Modern Form

Why British Sculpture Matters Today

Sculpture has always held a distinctive place in British art, shifting from traditional monuments to bold explorations of form, space, and concept. In the 20th century, figures such as Barbara Hepworth and Henry Moore brought international recognition to British sculpture, carving a path that still shapes how artists work today. Their vision helped transform sculpture from being primarily commemorative to becoming a field of modern art where ideas, materials, and human experience are constantly redefined.

In the contemporary art world, British sculptors continue to push the boundaries of what sculpture can be. From monumental public works that dominate landscapes to intimate installations exploring themes of memory, identity, and material culture, today’s artists address a wide range of subjects with striking originality. The rise of conceptual art has expanded the possibilities further, challenging expectations and making sculpture one of the most dynamic areas of creative practice.

As we trace the role of British artists in shaping modern form, it becomes clear that contemporary sculpture is not simply about objects in space, but about conversations with history, place, and the people who encounter the work.

Lineage, from the 20th century to Now

The Shift in British Sculpture during the 20th Century

Before the emergence of modern art in Britain, sculpture was often tied to tradition and commemoration. Statues honoured monarchs, military figures, and civic leaders, with little space for abstraction or conceptual exploration. The 20th century marked a turning point. Artists began to look beyond representation, focusing instead on form, material, and emotion. This was the moment when sculpture entered conversations with wider art movements, and Britain’s role in shaping the global art world became impossible to ignore.

Barbara Hepworth: Form, Landscape, and Abstraction

Barbara Hepworth was one of the leading figures in redefining British sculpture. Working with stone, wood, and bronze, she sought purity in form and often carved directly into her chosen materials. Hepworth’s sculptures frequently referenced the natural world, with pierced forms and smooth surfaces that seemed to echo the rhythms of landscapes around her.

Her move to St Ives in Cornwall during the Second World War placed her at the heart of a new community of British artists. The coastal landscape influenced her work profoundly, giving it a sense of place and timelessness. Today, her legacy continues through The Hepworth Wakefield, a museum dedicated to her practice, which also showcases contemporary British sculptors building upon her influence. Hepworth’s commitment to abstraction and her sensitivity to material remain vital to the language of British sculpture.

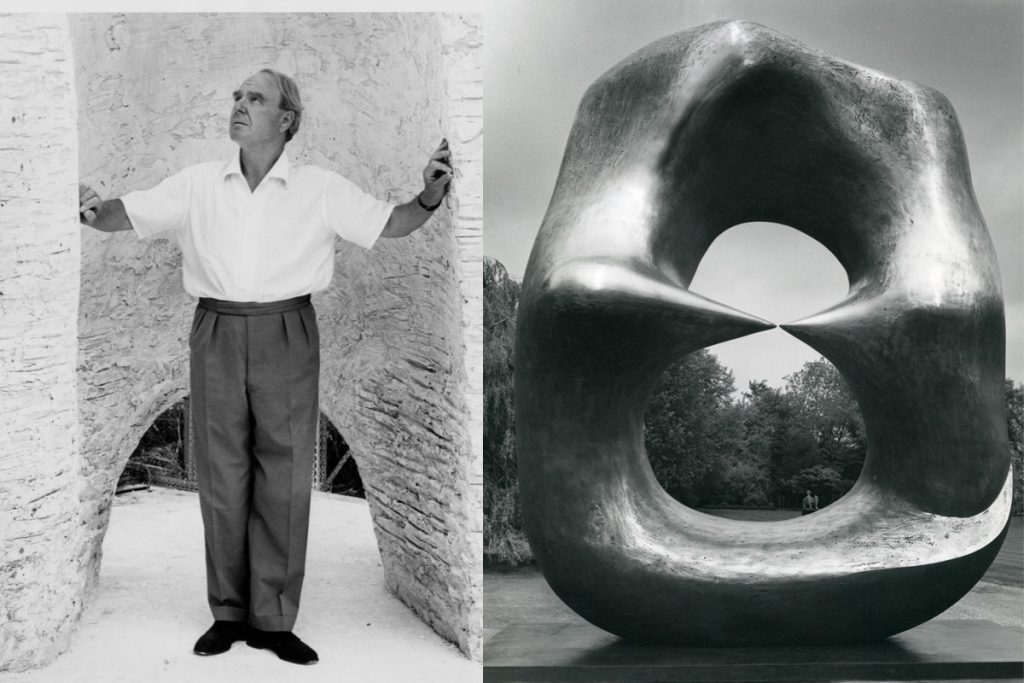

Henry Moore: Human Form and Monumentality

While Hepworth was refining abstraction through intimacy with material, Henry Moore pursued scale, presence, and universal symbolism. Moore’s reclining figures, mother-and-child forms, and monumental bronzes connected deeply with both human experience and landscape. His sculptures were not confined to galleries; they were placed in public parks, civic spaces, and international exhibitions, giving them extraordinary reach.

Moore’s role in shaping British art extended beyond the works themselves. His ability to balance figuration with abstraction made his practice both accessible and experimental. The Henry Moore Foundation and the Henry Moore Institute in Leeds ensure that his contributions remain central to research, exhibitions, and public understanding of British sculpture. His influence continues to resonate with contemporary sculptors who grapple with questions of form, scale, and public presence.

Building a Legacy for Contemporary Practice

Together, Barbara Hepworth and Henry Moore laid the groundwork for the wide range of practices that define British sculpture today. Their work in the mid-20th century helped Britain gain recognition on the international stage, and their legacy created a fertile space for the conceptual art movements of the 1970s and beyond.

The significance of their contributions lies not only in the sculptures themselves but also in how they expanded the possibilities of the medium. They made sculpture a language capable of exploring themes far beyond representation, opening the door for British artists to engage with identity, politics, memory, and materiality in ways that still shape the art world.

Exploring Themes that Shape Today’s Practice

The Rise of Conceptual Art in British Sculpture

By the 1970s, British sculpture had entered new territory. Artists began to move away from traditional carving and casting, embracing ideas and processes that blurred the boundaries between sculpture, installation, and performance. This period was shaped by conceptual art, which placed greater emphasis on meaning than on material. In this context, sculpture became a way to challenge perceptions, provoke dialogue, and explore the unseen structures of society.

Conceptual art’s role in shaping British sculpture was profound. It redefined what the medium could be, making it as much about the space around an object as the object itself. For many British artists working today, these shifts laid the foundation for exploring themes of memory, identity, politics, and the everyday.

Rachel Whiteread: Memory and the Poetics of Space

Rachel Whiteread emerged in the 1990s as one of the most influential British sculptors of her generation. She is best known for casting the negative spaces of ordinary objects and buildings, turning absence into form. Works such as House (1993), a concrete cast of the interior of a Victorian terrace in London, transformed a demolished home into a monument to memory and loss.

Whiteread’s practice demonstrates how sculpture can be deeply conceptual while remaining visually striking. By focusing on voids and absences, she gives physical presence to spaces that usually go unnoticed. Her approach reflects a distinctly British way of exploring themes tied to history, memory, and place.

Mona Hatoum: The Politics of the Everyday

Mona Hatoum’s work exemplifies how British sculpture can engage with global themes through a personal lens. Born in Beirut and later based in London, Hatoum uses everyday objects to create sculptures and installations charged with tension. Items such as kitchen utensils, beds, or maps are transformed into unsettling works that reflect ideas of displacement, conflict, and identity.

Her art operates at the intersection of the personal and the political. By reshaping domestic objects into threatening or fragile structures, Hatoum highlights how the familiar can carry hidden layers of meaning. In doing so, she shows how British artists can use sculpture as a platform for addressing universal concerns within the framework of contemporary art movements.

Cornelia Parker: Transformation and Rupture

Cornelia Parker has become renowned for works that explore destruction, transformation, and material states. One of her most celebrated pieces, Cold Dark Matter: An Exploded View (1991), involved suspending the fragments of a garden shed that had been blown up by the British Army. Lit from within, the fragments cast shadows across the gallery walls, creating an immersive and unsettling environment.

Parker’s art demonstrates how British sculpture embraces experimentation with materials and concepts. By using acts of rupture, she reframes the ordinary, asking viewers to confront ideas of fragility, violence, and reconstruction. Her practice shows how sculpture has expanded into experiences that are as much about atmosphere as about objects.

A Wide Range of Themes in Contemporary Practice

Whiteread, Hatoum, and Parker represent only part of the wide range of themes shaping British sculpture today. Contemporary artists continue to explore the body, landscape, politics, ecology, and identity, building upon the lineage of Hepworth and Moore while embracing the open-ended possibilities introduced by conceptual art.

This thematic diversity demonstrates how British art has evolved over the past century, moving from a focus on form and material towards a dynamic field that engages directly with society, culture, and lived experience.

Materials and Methods, from Bronze to Polymers

From permanence to experimentation

Sculpture has long been linked with permanence. Bronze, stone, and marble once defined the medium, conferring authority and endurance. Yet as British art moved into the 20th century, these materials were no longer treated as unquestionable. Artists such as Barbara Hepworth and Henry Moore continued to work with stone and bronze, but they carved, cast, and placed their sculptures in ways that redefined how these materials spoke to audiences. This questioning attitude opened the door for later generations to expand the vocabulary of sculpture beyond traditional choices.

Phyllida Barlow: using the everyday

Phyllida Barlow became renowned for using ordinary and inexpensive substances such as plywood, plaster, and cardboard. She scaled these materials up into vast installations that filled galleries with towering forms. By doing so, she disrupted the expectation that sculpture should be pristine, permanent, or polished. Her works invited people to consider weight, balance, and fragility, but through the lens of materials usually overlooked or discarded. Barlow showed how the everyday could become monumental, shifting attention from tradition to imagination.

Rebecca Warren: raw energy in clay and bronze

Rebecca Warren approaches material with both irreverence and intensity. Clay is often her starting point, shaped into figures that feel deliberately rough and expressive. When cast into bronze, these forms retain their raw gestures, creating tension between the immediacy of clay and the durability of metal. Warren frequently references art history in playful and provocative ways, questioning the authority of past sculptors while adding her own humour and vitality. Her practice demonstrates how traditional materials can still be reinvented when handled with bold intent.

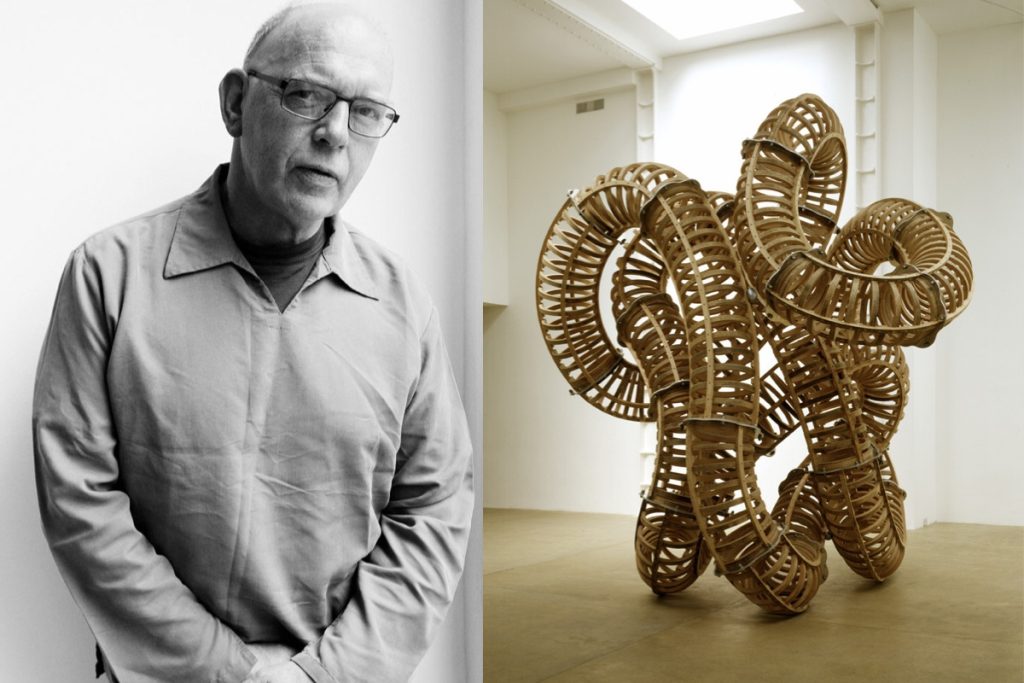

Richard Deacon: engineering and process

Richard Deacon is recognised for treating sculpture as a form of construction. Working with laminated wood, stainless steel, and synthetic plastics, he creates looping, twisting forms that combine technical precision with organic rhythm. Collaboration with fabricators is central to his method, showing how process itself becomes part of the artwork. Deacon’s approach highlights the shift in British sculpture towards treating materials not simply as a medium, but as part of a dialogue between artist, technology, and structure.

Helen Marten: assembling new narratives

Helen Marten belongs to a younger generation that treats materials as carriers of meaning. Her assemblages combine wood, ceramics, textiles, and everyday objects, resulting in dense and layered works. These sculptures often resist straightforward interpretation, encouraging viewers to trace connections between fragments. Marten’s Turner Prize win in 2016 confirmed her as a leading voice in contemporary British art, with a practice that shows how sculpture can blend conceptual ideas with the tactile presence of diverse materials.

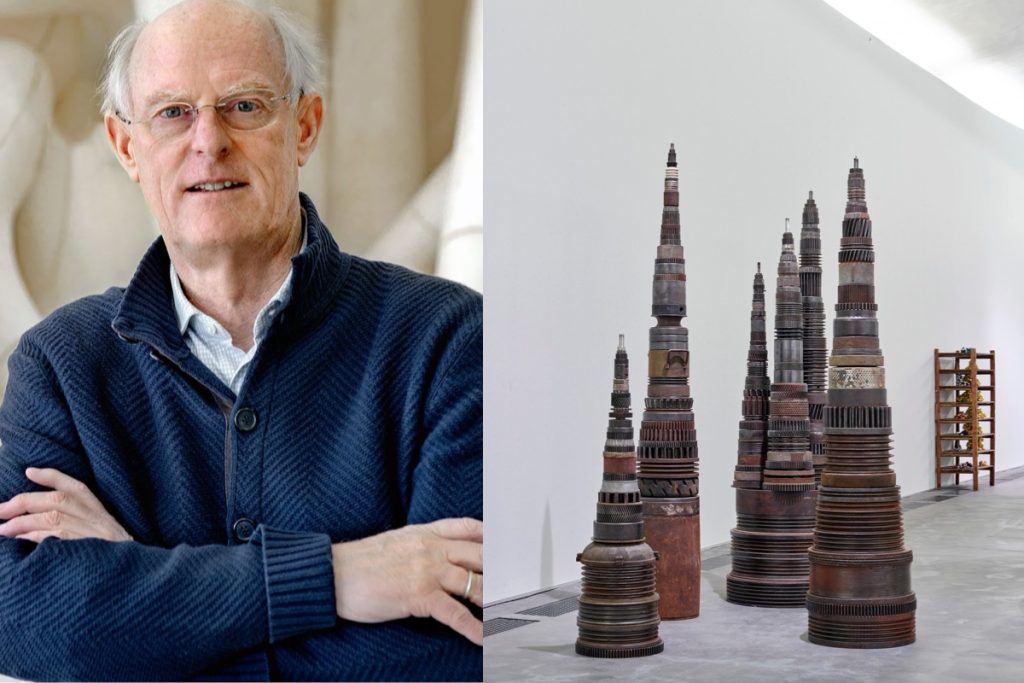

Tony Cragg: transformation and abstraction

Tony Cragg began by arranging found plastics into striking patterns, giving throwaway materials new life. Over time, he moved towards polished bronzes, steel, and wood, but always with an eye for transformation. His abstract, flowing forms suggest matter caught in motion, as if solid materials could shift and morph before our eyes. Cragg’s work illustrates how sculpture can explore both scientific and organic processes through material innovation.

Conrad Shawcross: machines as sculpture

Conrad Shawcross takes inspiration from engineering and mathematics. His sculptures often incorporate gears, lights, and motion, functioning like machines that blur the line between art and technology. Works such as Paradigm outside the Francis Crick Institute in London demonstrate how mechanics can become aesthetic, turning structural design into visual poetry. Shawcross represents a strand of British sculpture where curiosity about science shapes artistic form, showing that materials can be both functional and symbolic.

A new material landscape

What connects these artists is not a single style, but a shared willingness to rethink materials. Traditional substances such as bronze and wood remain part of the sculptural language, yet they sit alongside cardboard, plastics, textiles, and engineered systems. Each choice of material carries meaning, whether permanence, fragility, familiarity, or innovation. The story of British sculpture today is, in many ways, the story of how materials themselves have become central to artistic thought.

Public Space and Place

Why public sculpture matters in Britain now

Public sculpture in Britain does more than decorate a site. It changes how people move, talk, and identify with a place. When artists work at civic scale, materials meet everyday life. The result is art that belongs to everyone, not only to those who visit galleries.

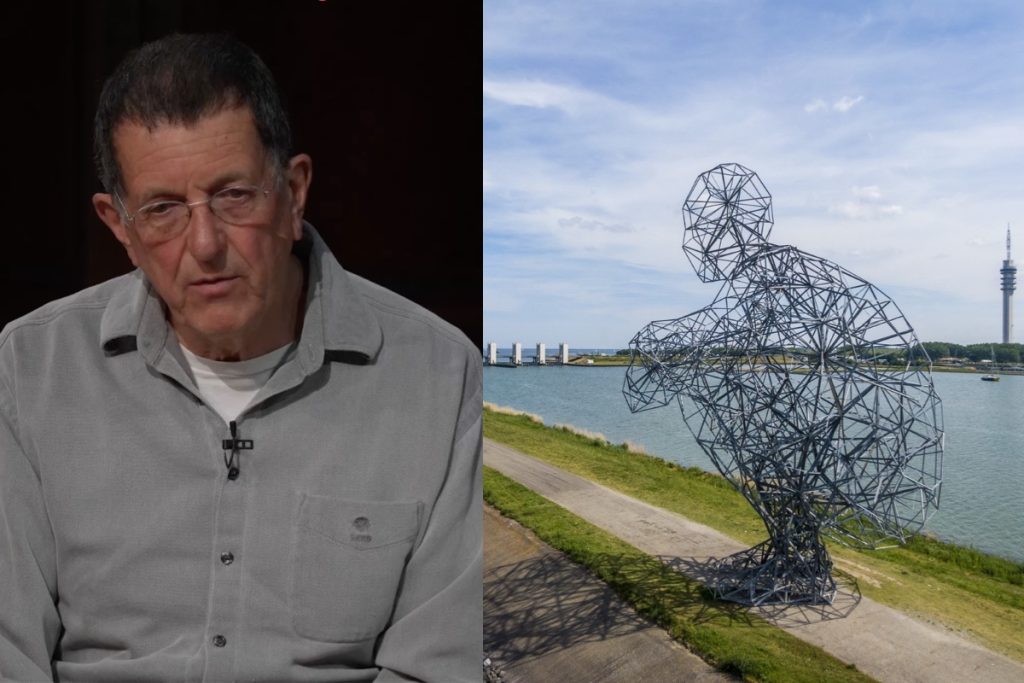

Angel of the North, identity and scale

Antony Gormley’s Angel of the North in Gateshead has become a defining landmark for the North East. It is widely understood as a symbol of regional pride, created with the clear brief of making an ambitious work that would speak for the area. The sculpture’s presence beside the A1 means millions encounter it as part of daily life. Its success shows how a single work can carry place, memory, and welcome in one image.

ArcelorMittal Orbit, engineering and spectacle

Designed by Anish Kapoor with Cecil Balmond, the ArcelorMittal Orbit rises over Queen Elizabeth Olympic Park in Stratford. At 114.5 metres, it is the tallest sculpture in the UK, combining viewpoint, structure, and artwork in one. Visitors can ride the tower’s helix slide or take in the panorama from the viewing deck. The piece is both icon and experience, a reminder that contemporary British sculpture often works through engineering as much as through form.

The Fourth Plinth, a civic conversation in Trafalgar Square

The Fourth Plinth programme turns a single pedestal into an open conversation about the art world and the life of the city. The current commission by Teresa Margolles, titled Mil Veces un Instante, was unveiled in September 2024 and remains the live installation on the plinth. The programme invites debate, research, and public curiosity, with future commissions selected from shortlists that have included British sculptors such as Thomas J Price and Veronica Ryan.

Yorkshire Sculpture Park, landscape as gallery

Yorkshire Sculpture Park offers a 500 acre estate where sculpture meets landscape. Visitors encounter works by British and international artists across fields, lakes, and woodland, with indoor galleries that extend the experience. YSP describes itself as a leading international centre for modern and contemporary sculpture, a claim supported by its long history and awards for visitor experience. The setting changes how works are read, since weather, seasons, and distance become part of the composition.

Sculpture in the City, art in the Square Mile

Each year, Sculpture in the City brings contemporary works to the streets of London’s financial district. The project turns the urban realm into a rotating outdoor gallery, free to explore. The 2025 edition begins in mid July and runs into 2026, adding new encounters to routes many people already walk for work. This initiative shows how partnerships between artists, curators, and city stakeholders can give sculpture a natural audience.

How setting shapes meaning

Public settings alter how sculpture works. A rural park encourages slow looking. A busy square demands instant clarity. A transport corridor creates repeat encounters over years. In each case, the site shapes interpretation. British artists understand this, which is why the strongest public works engage with history, access, and daily rhythms as carefully as they do with material and form.

The Artists Shaping Modern Form Now

Antony Gormley: the body and space

Antony Gormley is one of the most recognisable British sculptors of our time. His work uses the human body as a starting point, often casting his own figure to explore how people relate to space. Pieces such as the Angel of the North and Another Place on Crosby Beach show how sculpture can operate both as landmark and meditation on human presence. Gormley’s practice consistently asks where the body belongs in the modern world, and his work has become central to discussions about the role of public sculpture in Britain.

Anish Kapoor: voids and reflective surfaces

Anish Kapoor creates sculptures that play with perception. Using materials such as polished steel, pigments, and engineered structures, he explores ideas of emptiness, reflection, and infinity. Works like Cloud Gate in Chicago and the ArcelorMittal Orbit in London are both visually striking and conceptually ambitious. Kapoor’s ability to merge engineering with aesthetic experience positions him as a figure whose influence extends across the art world.

Rachel Whiteread: absence as form

Rachel Whiteread’s practice centres on casting negative space, transforming absence into presence. By creating concrete or resin casts of interiors and everyday objects, she brings attention to memory and the traces of life. Her Turner Prize-winning approach highlights how conceptual art can remain deeply emotional and connected to human experience.

Cornelia Parker: transformation through destruction

Cornelia Parker is known for works that use acts of rupture as their starting point. Her suspended installation Cold Dark Matter: An Exploded View turned a garden shed into a constellation of fragments. Parker shows how destruction can lead to new forms of beauty, and how ordinary materials can be made extraordinary. Her work continues to expand what sculpture means in contemporary British art.

Phyllida Barlow: monumental from the ordinary

Phyllida Barlow challenged conventions by using simple, everyday materials on an enormous scale. Her installations filled galleries with towering, rough-edged constructions that invited viewers to navigate through precarious environments. Barlow’s practice demonstrated that sculpture did not need to be polished or permanent to have impact, leaving a strong influence on younger British artists.

Mona Hatoum: displacement and tension

Mona Hatoum’s work addresses themes of identity, conflict, and belonging. By transforming domestic objects into unsettling installations, she connects the personal with the political. Her sculptures carry both vulnerability and menace, reminding us that British art often speaks to global issues while grounded in lived experience.

Yinka Shonibare CBE RA: identity and global histories

Yinka Shonibare combines references to colonial history with vibrant use of Dutch wax textiles. His sculptures often take classical forms but dress them in patterned fabrics that question ideas of identity, power, and representation. Public commissions such as his Nelson’s Ship in a Bottle for the Fourth Plinth highlight his ability to connect art history with contemporary social debate.

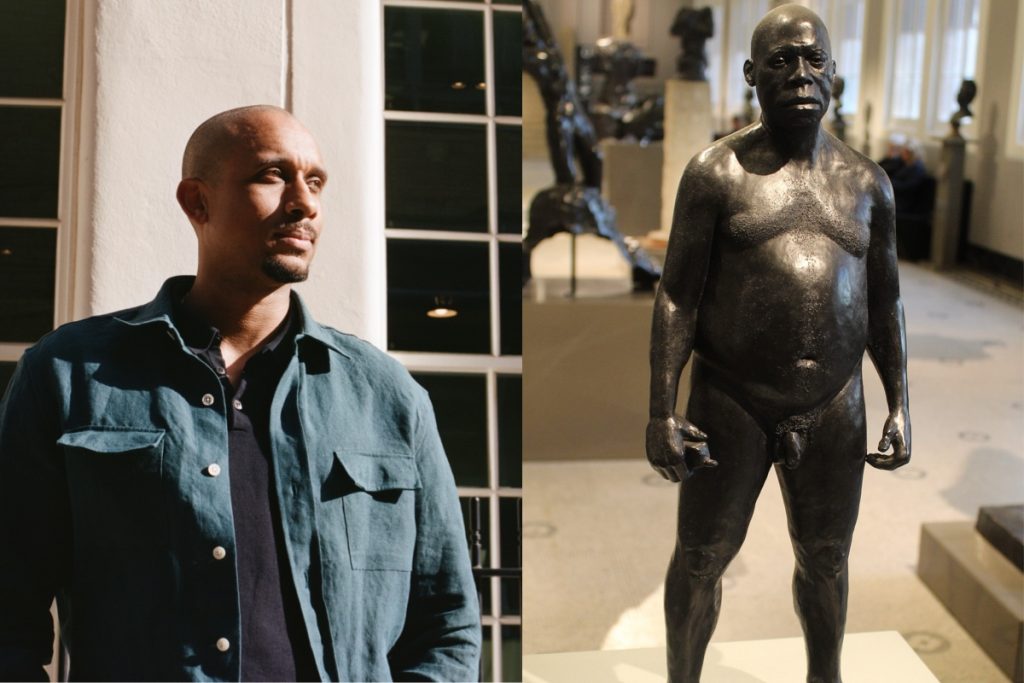

Thomas J Price: representation in public space

Thomas J Price creates figurative sculptures that challenge traditional monuments. His works often depict everyday people, giving presence and dignity to figures who are usually absent from civic sculpture. By placing these works in public spaces, Price reframes questions about who deserves representation and how monuments shape cultural memory.

Veronica Ryan: memory in material

Veronica Ryan works with organic and handmade materials, often referencing memory, healing, and cultural identity. Her Turner Prize-winning installations combined textiles, seeds, and everyday objects, reflecting on migration and belonging. Ryan’s practice shows how quiet, intimate materials can carry powerful resonance in the art world.

Jesse Darling: fragile structures and critique

Jesse Darling, winner of the Turner Prize in 2023, creates works that appear fragile or makeshift. Using materials such as steel, concrete, and found objects, Darling builds unstable structures that reflect on vulnerability and social systems. Their work demonstrates how sculpture can critique institutions while remaining visually inventive.

Helen Marten: complexity and assemblage

Helen Marten constructs intricate assemblages from diverse materials, layering objects and references into enigmatic compositions. Her Turner Prize win in 2016 confirmed her position as one of the most important voices in contemporary British art. Marten’s work shows how sculpture today can be playful, intellectual, and materially adventurous all at once.

Tony Cragg: abstract forms in motion

Tony Cragg’s sculptures often appear as if solid matter is in flux. Whether using wood, bronze, or steel, he creates biomorphic forms that suggest growth, movement, and transformation. Cragg’s ability to move from found objects to large-scale polished abstractions reflects the adaptability and innovation of British sculptors.

Rebecca Warren: irreverence and tradition

Rebecca Warren’s rough, expressive figures in clay and bronze challenge the smooth perfection often associated with sculpture. Her works are filled with humour and raw energy, drawing on art history while undermining its conventions. Warren demonstrates how irreverence can sit alongside tradition, offering a fresh perspective on the role of materials and form.

Conrad Shawcross: science, technology, and light

Conrad Shawcross brings scientific and mathematical ideas into sculpture. His works often use light, mechanics, and engineered systems to explore patterns and perception. Pieces such as Paradigm in London show how contemporary sculpture can merge with architecture and technology, expanding what is possible within the field.

A wide range of voices shaping British sculpture

Together, these artists illustrate the diversity of contemporary British sculpture. Some work with the body, others with technology, some with history, and others with fragile everyday materials. What unites them is a willingness to test the limits of sculpture, ensuring that British art continues to play a central role in shaping modern form.

Where to Experience British Sculpture, A Practical Guide

Tate Britain and Tate Modern

Tate Britain holds one of the most important collections of British art from the 16th century to today, with sculpture forming a key part of its displays. Works by Henry Moore, Barbara Hepworth, and Jacob Epstein sit alongside contemporary commissions, showing how British sculpture has developed over time. Across the river, Tate Modern brings together global perspectives with large-scale installations and works by artists such as Phyllida Barlow, Cornelia Parker, and Mona Hatoum. For anyone interested in how sculpture sits within wider art movements, these two institutions provide an essential starting point.

The Hepworth Wakefield

Dedicated to the life and legacy of Barbara Hepworth, The Hepworth Wakefield is one of the UK’s leading centres for modern and contemporary sculpture. Its galleries not only house Hepworth’s iconic works but also present exhibitions by emerging and established artists. The museum’s riverside setting and carefully designed architecture make it a destination where the dialogue between space, form, and material feels particularly vivid.

Henry Moore Institute, Leeds

For those wishing to study sculpture in greater depth, the Henry Moore Institute in Leeds offers galleries, a specialist library, and an archive dedicated to research into the medium. It is not only a place to view exhibitions but also to explore the scholarship that continues to shape our understanding of British sculpture. The institute has become a hub for both academic inquiry and public engagement, extending Moore’s legacy into the present.

Yorkshire Sculpture Park

Spanning over 500 acres, Yorkshire Sculpture Park remains the most ambitious open-air gallery of its kind in the UK. Visitors encounter works by Henry Moore, Barbara Hepworth, and contemporary sculptors such as Tony Cragg and Ai Weiwei, set within fields, woodland, and lakes. The combination of art and landscape creates changing experiences across seasons, making each visit different. YSP illustrates how sculpture interacts with environment in ways that gallery walls cannot replicate.

Sculpture in the City, London

Each summer, Sculpture in the City transforms London’s financial district into an outdoor gallery. International and British sculptors present works that sit alongside skyscrapers, office squares, and ancient churches, creating a striking contrast between art and architecture. The programme changes annually, meaning visitors encounter new works each year while also witnessing how the same urban setting can reshape interpretation.

Frieze Sculpture, Regent’s Park

Frieze Sculpture, staged each autumn in Regent’s Park, offers another chance to see contemporary sculpture outside traditional gallery spaces. The exhibition gathers works by British and international artists in the open air, complementing the major art fair that takes place nearby. It provides a snapshot of current directions in sculpture, accessible to all who walk through the park.

Regional museums and smaller initiatives

Beyond the major institutions, British sculpture thrives in regional museums, university galleries, and independent spaces. From the Barbara Hepworth Museum in St Ives to projects such as the Cass Sculpture Foundation in West Sussex (now closed but still influential in shaping dialogue), local contexts continue to play a key role in giving sculpture visibility. Community-led projects also bring works into high streets, schools, and public squares, ensuring access is not limited to national centres.

Why visiting matters

Reading about sculpture offers one perspective, but standing before the works provides another. The weight of materials, the scale of forms, and the dialogue with environment can only be fully understood in person. Britain offers a wide range of opportunities to do this, from landmark museums to outdoor parks and city-centre installations. For anyone interested in how sculpture continues to shape modern form, these experiences are vital.

Case Studies, How Ideas Meet Materials

Rachel Whiteread: turning absence into memory

Rachel Whiteread’s House (1993) remains one of the most significant British sculptures of the late 20th century. By casting the interior of a terraced house in East London, she transformed an ordinary dwelling into a monument of absence. The concrete form recorded every trace of the building’s interior, from staircases to windows, freezing the negative space into permanence. Although controversial at the time, the work became a touchstone for how sculpture can address memory, loss, and the changing fabric of urban life. Whiteread’s practice demonstrates how conceptual art can be deeply personal, turning the overlooked into something monumental.

Yinka Shonibare: rethinking history through fabric

Yinka Shonibare’s Nelson’s Ship in a Bottle (2010), created for the Fourth Plinth in Trafalgar Square, reimagined naval history with a playful yet critical eye. The piece featured a detailed replica of Admiral Nelson’s flagship, HMS Victory, but with sails made from Dutch wax textiles commonly associated with African identity and colonial trade. By blending historical reference with contemporary materials, Shonibare asked viewers to reconsider Britain’s imperial past and its continuing cultural echoes. The sculpture became an emblem of how British art can use humour, colour, and craft to engage with complex histories in public space.

Thomas J Price: representation in the public realm

Thomas J Price has gained recognition for creating figurative sculptures that represent people often absent from public monuments. His works include depictions of everyday individuals, scaled to the size and presence usually reserved for historic leaders. By placing these figures in civic contexts, such as the bronze sculpture Reaching Out in London’s East End, Price redefines who deserves visibility. His practice shows how contemporary sculpture is not only about materials and form, but also about social justice, civic memory, and the politics of space.

A Living Tradition of Innovation

Contemporary British sculpture draws strength from its past while continually reinventing itself. The foundations laid by Barbara Hepworth and Henry Moore in the 20th century created a language of form and abstraction that still resonates. Yet the generations that followed have expanded this language, moving into conceptual art, embracing new materials, and exploring themes that reflect the realities of modern life.

From monumental public landmarks such as Antony Gormley’s Angel of the North to the intimate materiality of Veronica Ryan’s installations, British artists reveal the wide range of possibilities sculpture offers. Some draw from engineering and science, like Conrad Shawcross, while others reflect on identity and history, like Yinka Shonibare and Thomas J Price. What unites them is a commitment to testing limits, creating works that speak to society as much as to the art world.

Sculpture in Britain today is not confined to galleries or pedestals. It inhabits fields, city squares, museums, and memory itself. It challenges, questions, and transforms how we understand our environment and our place within it. For anyone exploring modern art, British sculpture offers one of the richest and most dynamic traditions, alive with innovation and deeply engaged with the present.

Leave a Reply