No products in the cart.

Futurism in Art: How Artists Captured Speed, Industry and the Machine Age

At the dawn of the twentieth century, the world was shifting at a dizzying pace. Cities buzzed with the clang of streetcars and the hum of electricity. The rhythmic churning of factory machines filled the air as steel bridges rose and railways stitched continents together. This was not just the birth of modern industry; it was the beginning of a new way of seeing.

In 1909, Italian poet Filippo Tommaso Marinetti put this transformation into words. Published on the front page of Le Figaro, his Futurist Manifesto was a fiery call to abandon the past and embrace the speed, dynamism and mechanical power of the modern world. He rejected museums and classical traditions in favour of motion, technology and raw energy.

From this explosive declaration, Futurism emerged not just as an art movement, but as a radical way of living and creating. It celebrated cars, aeroplanes, electricity and even war, seeing each as symbols of progress and human strength. The artists who followed Marinetti’s lead sought to reimagine every aspect of visual culture. Among them, painter and sculptor Umberto Boccioni worked to depict the physical sensation of movement in form. Giacomo Balla also explored the visual rhythms of speed and light, producing works that fractured time across the canvas.

Together, these figures gave Futurism its pulse. They did not merely reflect the machine age; they were determined to become its voice, its vision and its fuel.

The Manifesto and Its Vision

In February 1909, the front page of Le Figaro, one of France’s most influential newspapers, printed a bold and incendiary declaration. Penned by the Italian poet Filippo Tommaso Marinetti, The Futurist Manifesto was not a gentle invitation to contemplate beauty. It was a shout, a challenge, and a provocation. In it, Marinetti proclaimed that speed, machinery, violence, and youth were the new ideals for a world shedding the skin of its past.

This manifesto did not emerge in a vacuum. Across Europe and beyond, the world was transforming. Steam engines had redefined mobility. Mass production lines were beginning to dominate industrial cities. Electricity and the telephone were shrinking the world’s distances. Against the backdrop of the Industrial Revolution’s legacy, Marinetti saw the artist’s role shifting. No longer should creators look backwards to Renaissance harmony or classical repose. Instead, they were to forge ahead into the chaos and energy of modern life.

He spoke of a love for danger and daring. He celebrated the roaring motor car as more beautiful than classical sculpture. His vision of the future was unapologetically aggressive, and through his poetry, essays, and public performances, he urged artists to reject nostalgia and tradition.

Futurism’s embrace of the machine age was not just aesthetic. It was philosophical. For Marinetti, modernity required a reworking of human history itself. It was a break from the past, a reset. Art, once grounded in static representation, would now move in sync with the rhythms of the city, the factory, and the crowd. His activism was entwined with artistic revolution, pushing a whole generation of painters, sculptors, and designers to follow suit.

Painting Speed and Energy: Futurist Art in Motion

In a world where steam trains howled across tracks and electricity buzzed through cities, Futurist artists set out to translate energy into visual form. They did not want to paint what things looked like. They wanted to paint how things felt when they moved. This radical shift gave rise to some of the most dynamic and physically charged artworks of the twentieth century.

One of the most iconic examples is Umberto Boccioni’s Unique Forms of Continuity in Space (1913). This bronze sculpture is not a still figure but a body in flux. It strides forward, its limbs almost swallowed by the air currents that trail behind it. Rather than represent a person, Boccioni sculpted movement itself. He wanted the viewer to feel the forward thrust of progress and to glimpse the future in metal and form.

Another pioneer of motion in art was Giacomo Balla. In his painting Abstract Speed + Sound, Balla used fractured shapes, repeated forms, and rhythmic lines to suggest the pulse of a speeding car. In Street Light, he portrayed an ordinary streetlamp not as a fixture but as an explosion of electric rays, radiating colour and sound into the night. These works pushed painting into a new sensory realm, where light and speed were not just seen but experienced.

To achieve this kinetic energy, Futurist artists adopted techniques from other movements, including Divisionism. They broke down colours into small brushstrokes and used overlapping planes to suggest movement through time. This layering created a sense of vibration, of forms shivering into action. In many ways, they were trying to depict a world no longer defined by stillness but by perpetual motion.

Through their canvases and sculptures, the Futurists offered a visual language for a mechanised, accelerating age. Their art captured not only what was seen, but what was felt in the rush of the modern world.

Capturing Movement: Science Meets Art

In the early years of the twentieth century, art and science began to walk side by side. As trains picked up speed and machines pulsed with new energy, artists looked to technology not just for subject matter but for method. Among the most influential scientific developments was motion photography, pioneered by figures such as Étienne‑Jules Marey and Eadweard Muybridge.

Marey, a French physiologist, used chronophotography to capture sequences of movement in animals and humans. Muybridge, best known for his galloping horse series, proved that photography could dissect time and motion into a series of split seconds. For Futurist artists, this was revelatory. They no longer had to guess at how the body moved; they could see it, frame by frame.

This scientific approach directly inspired artworks like Giacomo Balla’s Dynamism of a Dog on a Leash (1912). In this painting, a dachshund trots forward, its legs and tail multiplied across the canvas. The woman’s feet, like the dog’s, repeat in rhythmic succession. The effect is both humorous and profound. Balla was not painting a dog, but the energy of walking the blur of limbs that our eyes often miss but the camera could freeze.

Futurist art, in this sense, mirrored the speed and fragmentation of modern life. Just as machines broke tasks into repetitive actions, artists fragmented forms to show motion. They used visual repetition to suggest continuous energy. Scientific tools like time-lapse photography gave them the evidence, while paint and sculpture gave them the means to explore it emotionally and physically.

This convergence of science and art gave Futurism its pulse. It allowed artists to turn fleeting action into lasting form, giving movement a visual identity that resonated with the pace of an industrialising world.

Sculpture Breaks Free

Futurist sculpture marked a decisive turn in modern art. Until this moment, sculpture had largely remained tied to traditional ideals of stillness and permanence. That changed when Umberto Boccioni, one of the key voices of the Futurist movement, moved beyond painting and began to explore how energy could be captured in three dimensions.

His most iconic work, Unique Forms of Continuity in Space (1913), presents a human-like figure caught mid-stride, limbs merging into air, body shaped by motion. The surface is muscular and fluid, more like flowing metal than static flesh. This was not a portrait, but a form born from velocity. Boccioni called for an art that did not merely represent movement but embodied it. He wanted sculpture to fuse form, force, and environment into one continuous expression.

This idea of “sculptural continuity” stood at the core of Futurist three-dimensional work. Instead of carving isolated figures, artists like Boccioni shaped their forms to stretch, ripple, and absorb the surrounding space. In Synthesis of Human Dynamism, the human figure becomes a field of motion rather than a fixed object. In Development of a Bottle in Space, the ordinary shape of a glass bottle is reimagined as a swirling object with inner and outer curves that feel alive.

These experiments broke with the static traditions of marble and bronze. They introduced a new kind of perception, one that viewed motion as inseparable from the object itself. Sculpture was no longer frozen in time. It had become part of time, alive with the pulse of machinery, the beat of footsteps, and the restless energy of a changing world.

Architecture, Design and the Machine Aesthetic

Futurist thinking was never confined to the gallery. It spilled out into the built environment, proposing radical transformations of how people would live, move and inhabit space. One of the boldest voices in this architectural turn was Antonio Sant’Elia, whose visionary drawings imagined cities powered by electricity, dominated by colossal towers and endless movement. His proposal, La Città Nuova (The New City), was not just a set of building plans but a dramatic reimagining of urban life. Roads soared across multiple levels, buildings resembled turbines and generators, and there was no trace of nature to soften the angular, industrial lines.

Though Sant’Elia’s concepts were never realised, they had a deep and lasting influence. Elements of his ideas echoed in later movements such as Precisionism in the United States and parts of Art Deco and Bauhaus in Europe. These styles also celebrated the machine age, often blending technical clarity with visual rhythm. The straight lines, symmetry, and stylised forms of these movements show how Futurism helped shape a modern aesthetic that connected art, architecture, and industrial progress.

In practice, machine-inspired design filtered into both civic and domestic architecture. Factories, railway stations and even cinemas adopted streamlined features that reflected the speed and structure of the new world. In the United States, skyscrapers began to rise with stepped profiles and geometric detailing, suggesting motion and vertical aspiration. In Europe, architects experimented with exposed steel, reinforced concrete, and curtain walls, favouring function and bold form over ornamentation.

The Futurist ideal was to erase the past and embrace the present with unrelenting energy. Through architecture and design, they offered not just structures, but statements visions of how a civilisation powered by electricity, steel, and speed might look.

Futurism Beyond Painting

Futurism was never intended to be confined to canvas or marble. It was a total vision for life in the twentieth century. For its creators, especially Filippo Tommaso Marinetti, modernity meant a complete rupture from the past in every form of human expression. This conviction gave birth to a remarkable expansion of Futurism beyond visual art and into literature, music, theatre, film, food, and even urban planning.

One of the most radical innovations was Marinetti’s concept of Parole in libertà, or “words in freedom”. Rejecting traditional syntax and punctuation, these typographic experiments liberated language from the structure of grammar. Words exploded across the page in dynamic layouts that visually mimicked the chaos of modern life. These works anticipated modern visual poetry and graphic design.

Futurist music followed a similar path. Luigi Russolo, a painter turned composer, created what he called intonarumori acoustic noise machines that reproduced the sounds of industry, traffic, and war. His manifesto The Art of Noises argued that the musical world must reflect the sonic realities of modern life, from engines to sirens to gunfire. These ideas foreshadowed experimental electronic music and sound art.

On stage, Futurist theatre was short, jarring, and deliberately provocative. Performances abandoned realism in favour of abstraction, movement, and sensation. Scenery, lighting and even the actors themselves were part of a machine-like performance intended to shock and energise the audience. The plays often lasted only a few minutes, and some were completely silent.

In everyday life, Futurism attempted to infiltrate habits and customs as well. The Futurist Cookbook, published by Marinetti in 1932, proposed surreal and theatrical meals that completely abandoned traditional Italian cuisine. These included dishes shaped like airplanes, courses designed to stimulate multiple senses, and the banning of pasta as a symbol of sluggishness. Though satirical at times, the book was a sincere proposal to reimagine how modern people should eat.

Even the city was not immune to the Futurist touch. Urban planning proposals imagined cities built for velocity, verticality, and electricity. Every structure and road would serve movement, from people to data to goods. Although these visions were rarely realised in full, they helped lay conceptual groundwork for later developments in architecture and planning.

By reaching into so many domains of human activity, Futurism defined itself not just as an art movement, but as a philosophy of modern life. It sought to rewrite every part of experience for an age of machines, speed, and relentless change.

Context and Contradictions

While Futurism celebrated speed, innovation and the dynamism of the modern world, it was also deeply entangled in the political ideologies of its time. One of the most difficult aspects of the movement’s legacy lies in its association with nationalism and the rise of Fascism in Italy. Filippo Tommaso Marinetti, the founding voice of Futurism, was an outspoken nationalist who supported Italy’s entry into the First World War and later aligned himself with Benito Mussolini.

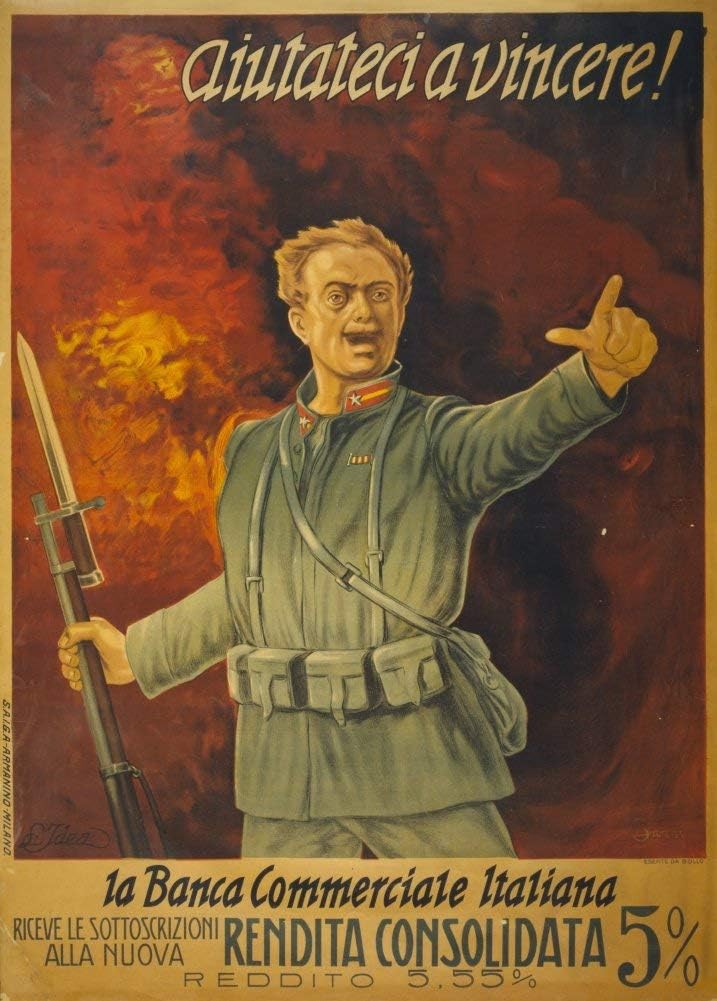

Marinetti’s embrace of militarism was not incidental. From the earliest texts, including the 1909 Futurist Manifesto, there was an aggressive exaltation of conflict and destruction. War was described as a cleansing force, necessary for renewal and progress. In this vision, art was not separate from society’s most violent instincts but was instead a catalyst for them. This glorification of force would later echo in the aesthetics of state propaganda and industrialised warfare.

These political entanglements raise serious ethical questions about the movement’s intentions and legacy. Was Futurism simply ahead of its time, pushing for technological and cultural evolution, or did it reflect a dangerous naivety about power and violence? The same love of machines and velocity that fuelled creative breakthroughs also overlapped with the brutality of mechanised war and oppressive regimes.

It is worth noting that not all Futurists followed Marinetti into Fascism. Some artists, like Umberto Boccioni, died in the First World War before the movement’s later political turn. Others, such as Giacomo Balla, eventually distanced themselves from politics altogether. Still, the shadow of ideology remains one of the most debated and uncomfortable aspects of Futurism’s history.

Today, this tension continues to provoke debate. Museums and scholars often grapple with how to present Futurist work that is both groundbreaking in form and troubling in ideology. The artworks remain admired for their innovation, but audiences are increasingly encouraged to consider the historical circumstances in which they were produced.

Understanding these contradictions does not mean rejecting the movement outright. Instead, it invites a fuller engagement with Futurism as a product of its time one that captured both the excitement and the anxiety of a century hurtling toward modernity.

Legacy and Global Impact

Futurism’s radical break from tradition left a deep imprint across the arts, long after its original wave had passed. The movement’s aggressive embrace of technology, speed and modernity influenced a wide variety of artistic responses around the world.

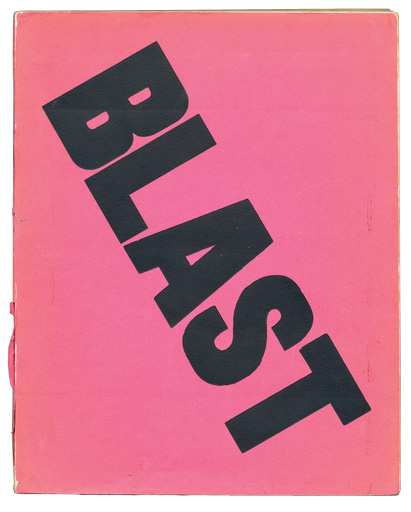

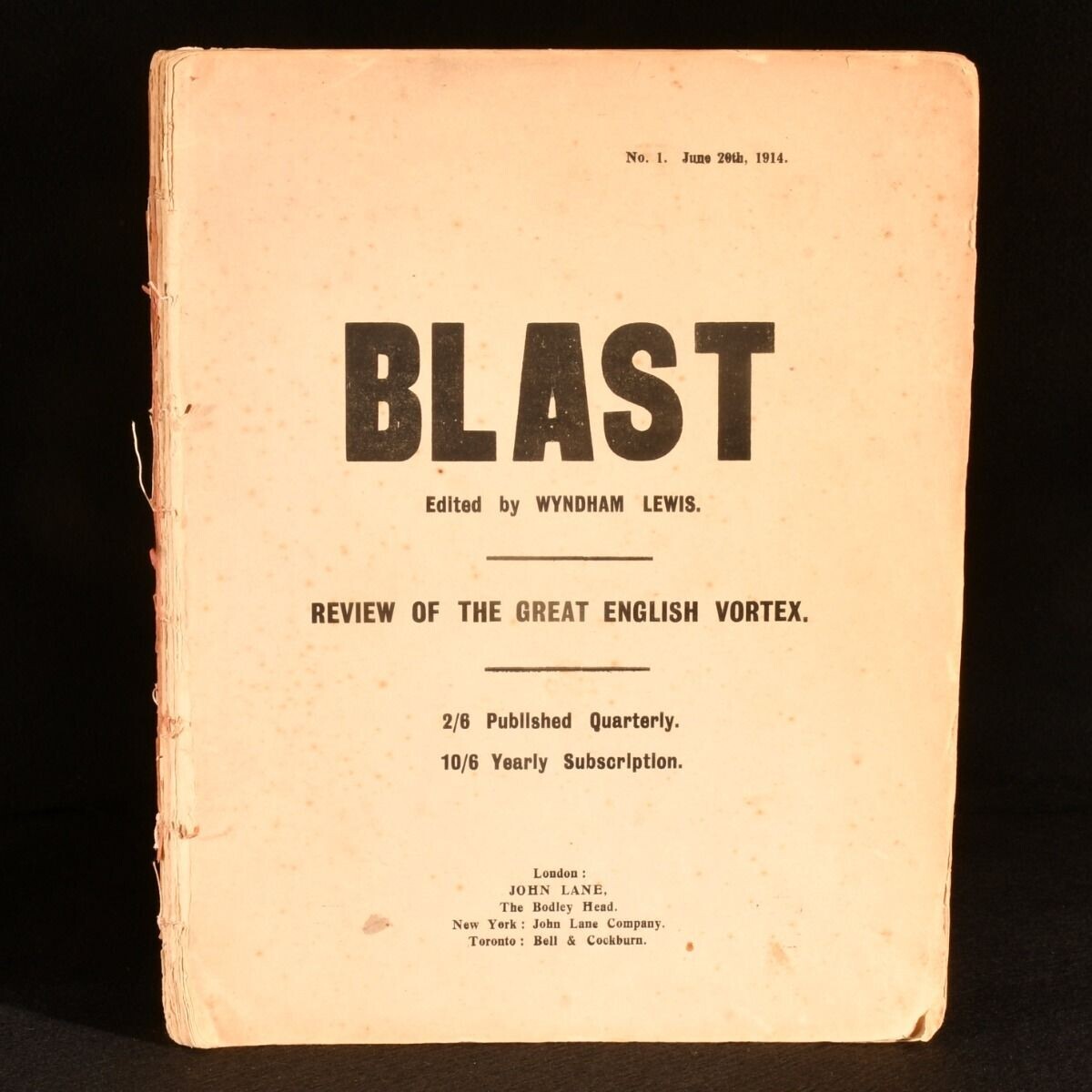

In Britain, Vorticism emerged as a response to Futurism. Artists such as Wyndham Lewis were inspired by the movement’s dynamism and abstraction, while also forging a more distinctly English aesthetic through their own publication, BLAST. Vorticism echoed Futurist themes but paired them with a sharper critique of social structures.

In Russia, the Futurist spirit took a new and distinct form. Russian Futurism, led by figures such as Vladimir Mayakovsky and Natalia Goncharova, blended visual experimentation with revolutionary politics. Although born separately from Italian Futurism, Russian Futurists similarly sought to destroy the old and make room for a new future, often drawing from their own cultural and linguistic traditions. Their impact helped shape Soviet Constructivism, another movement driven by a belief in industry and progress.

The ripples of Futurism were also felt in Surrealism, Dada, and even aspects of Abstract Expressionism. While these later movements often rejected Futurism’s love of war and nationalism, they built on its willingness to question reality, push boundaries, and integrate art with life.

In the modern age, traces of Futurist thinking are visible across popular culture and design. The angular forms and mechanical precision of Futurist painting can be seen in industrial design, fashion, and architectural renderings. Film genres like science fiction and cyberpunk carry forward the aesthetic of the machine-dominated future. Futurism’s visual language of movement and velocity also laid early groundwork for kinetic art and experimental animation.

The idea of Neo-Futurism emerged in the late twentieth and early twenty-first centuries, particularly in architecture. Designers such as Zaha Hadid and Santiago Calatrava revived the Futurist ambition to express technological progress through form. Skyscrapers, airports and even everyday infrastructure now echo the same aerodynamic elegance envisioned in the early drawings of Antonio Sant’Elia.

What endures most is the way Futurism challenged how art could represent time and transformation. In a world still fuelled by rapid change and innovation, its vision of artistic reinvention remains startlingly relevant.

The Speed of Creativity

Futurism’s legacy is not just a series of artworks, manifestos or exhibitions. It is a lens through which artists began to understand the modern world. At the heart of the movement was an obsession with acceleration cars, factories, electricity, communication. In capturing that energy, Futurist artists forced viewers to see art not as static, but as something alive and kinetic.

Whether in the silhouette of a modern skyscraper, the digital loops of motion graphics, or the tempo of high-speed urban life, Futurism continues to shape the way we engage with the world. Its ideas live on in how we frame motion, design cities, and visualise technology’s place in human experience.

As you explore the places, objects and artworks around you, look for echoes of that Futurist energy. It might appear in a video game interface, an advertising campaign, or the shape of a high-speed train. The interplay between creativity and technology is no longer radical, it is reality. And it all began with the vision of a few artists who believed the future could be drawn, sculpted and built into being.

Leave a Reply