No products in the cart.

10 Inspiring Landscape Photographers Who Capture Nature’s Beauty

Ask ten people to picture landscape photography and you will probably get ten different answers. For some it is dramatic mountain ranges and mirror calm lakes. For others it is a single tree in thick fog, or a line of sea foam sliding back across wet sand.

Landscape photographers are not just pointing cameras at pretty views. The best of them are patient editors of the real world, stripping away distraction until only the essentials of light, weather and place remain. They spend years revisiting the same headlands and valleys, learning how a location behaves through seasons and storms.

This guide is not about ranking the “best” landscape photographers. Instead, it introduces ten photographers who all approach nature’s beauty in distinct ways. Think of it as a tasting menu. You might not love every flavour, but each one will teach you something different about how to look at the world.

Before we meet them, it is worth touching on what makes landscape photography such a rich, and quietly demanding, way of working.

What landscape photography really pays attention to

Landscape photography looks simple until you try to do it. Anyone can stand in front of a view and press the shutter. The difference between a snapshot and a considered landscape image is usually three things.

First, timing. Not just pretty sunset light, but the relationship between light and weather at a particular place. Many landscape photographers will plan around small details, such as the ten minute window when a cliff face catches reflected light from the opposite valley, or the way mist pools in a hollow on cold mornings.

Second, editing in the field. A camera sees everything. A landscape photographer spends a lot of time deciding what to leave out. Tiny shifts in position can remove stray branches, merge distracting shapes or line up a curve in the foreground with a distant peak.

Third, a sense of story. The strongest images are not just about a location, but about a feeling. Loneliness, calm, scale, fragility, power. We respond less to “this is a famous mountain” and more to “this is what it felt like to stand here before the storm broke”.

Keep those three ideas in mind as you look at the work below. You will start to spot how differently each photographer answers those same questions of timing, editing and story.

1. Ansel Adams

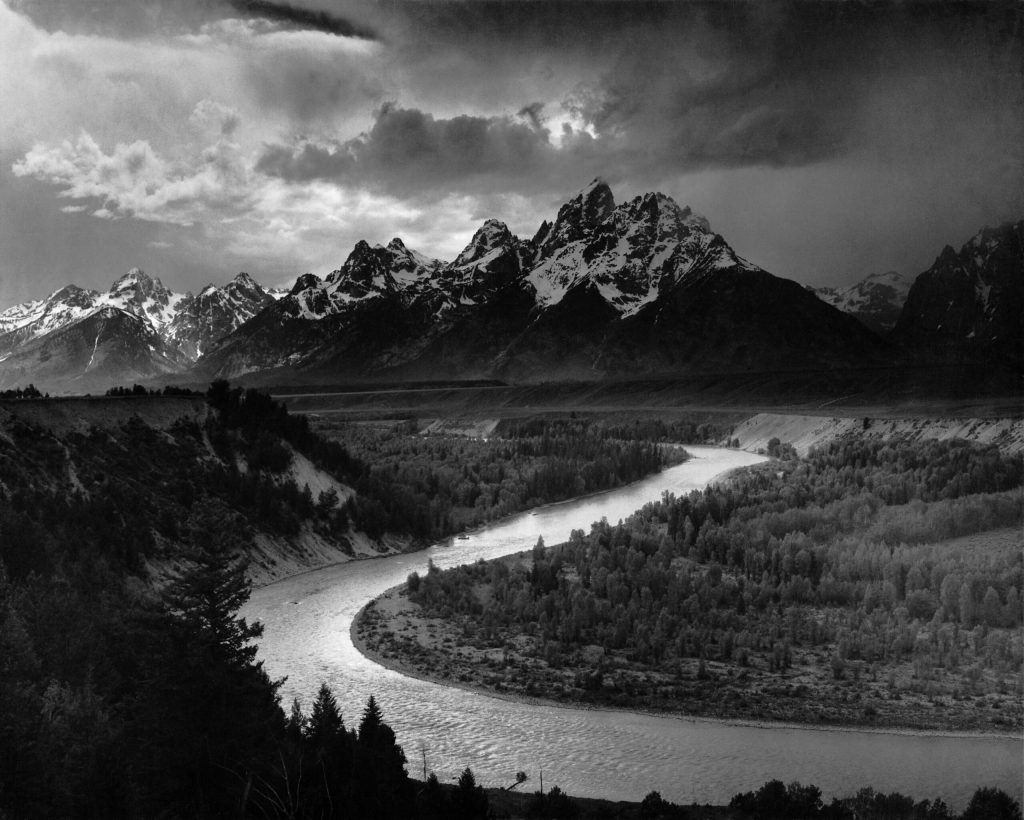

No list of inspiring landscape photographers is complete without Ansel Adams. He is the nearest thing the field has to a household name. Working mainly in the American West in the mid twentieth century, Adams produced the black and white images of Yosemite, the Sierra Nevada and the American national parks that have become visual shorthand for “wilderness”.

It is easy to think of his work as pure documentation. In reality, his images are very carefully controlled interpretations of nature. Adams used large format cameras, spot metering and a system of exposure and development that allowed him to place different parts of the scene at precise tonal values. He was effectively “scoring” light and shadow like music.

One detail that is not always obvious from online reproductions is how much delicacy there is in the mid tones. Up close, a good print of an Ansel Adams landscape has a surprising softness in the greys. The drama comes from how those gentle mid tones sit next to very clean highlights and deep, pure blacks.

If you are learning landscape photography, it is useful to look at Adams’ contact sheets and working prints, where available. You can see how much trial and error sat behind the famous frames, and how controlled the final choice was.

More of Ansel Adams’ work : https://www.anseladams.com

2. Joe Cornish

Closer to home, Joe Cornish is one of the most influential British landscape photographers of the last few decades. Based in North Yorkshire, his work ranges from grand views in the Highlands to intimate studies of moorland and coast.

Cornish often works with large format film, which encourages a slower, more deliberate approach. You can feel that pace in his images. Foregrounds are carefully structured, not cluttered. Lines of rock, water and shadow are arranged so that your eye moves through the frame almost without noticing.

A niche insight with Cornish is his use of “barely there” colour. He is not a fan of overly saturated hues. Instead, he often works with gentle colour contrasts: warm browns against cool greys, muted greens against a faintly pink sky. It is the sort of palette you see if you are genuinely out in the hills for hours, rather than the hyper saturated skies that only exist in camera presets.

Cornish also talks about the ethics of landscape photography, from access and erosion to how we describe wild places that are, in reality, heavily managed. That awareness sits quietly underneath the pictures and gives them a grounded, honest feel.

More of Joe Cornish’s work : https://www.joecornishgallery.co.uk

3. Rachael Talibart

Rachael Talibart has built an international reputation by focusing on one subject: the sea. Her seascape photography, much of it made on the south coast of England, turns storm waves and surf into almost sculptural forms.

She is best known for her “Sirens” series, in which huge breaking waves are caught at just the right moment to resemble mythological figures and creatures. It is not digital trickery. The forms are real, but you can tell from the timing that she has spent an absurd amount of time standing in weather most of us would avoid.

One quietly revealing thing in Talibart’s work is how often the horizon disappears. Rather than relying on the classic big sky and distant line where sea meets air, she frequently fills the frame with water and spray. That makes the images feel less like “views of the coast” and more like portraits of the sea’s surface.

If you photograph seascapes yourself, try borrowing that idea. Spend a session ignoring the sky, and build compositions that are almost entirely water, using shutter speed to control how much texture or blur you show.

More of Rachael Talibart’s work: https://www.rachaeltalibart.com

4. Thomas Heaton

Thomas Heaton is a British landscape photographer whose work many people first encounter through his long running YouTube channel. It would be a mistake to think of him only as a content creator though. His still images stand on their own: clean, thoughtful compositions that often favour quiet moods over drama.

Heaton spends a lot of time in woodland and along the coast, particularly in the north of England and Scotland. If you look through his projects, you will notice how often he photographs on days most of us would leave the camera at home: flat overcast light, drizzle, faint mist.

That choice is not laziness about getting up for sunrise. It is an understanding that complex scenes, especially woods, often photograph better without hard, contrasty light. Overcast conditions help colours sit together and make it easier to separate branches and trunks without everything turning into a chaos of highlights.

One niche detail that comes up in his behind the scenes videos is how often he abandons a shot. You will see him set up a tripod, work a composition for ten minutes, then walk away without pressing the shutter. That is a valuable habit to copy. Knowing when not to make an image is as important as knowing when to commit.

More of Thomas Heaton’s work : https://www.thomasheaton.co.uk

5. Michael Kenna

Michael Kenna is known for minimalist black and white landscapes that often feature man made structures within natural settings: power stations in mist, lone trees by industrial fences, piers stretching into fog.

He frequently works at night or in very low light, using long exposures that can run into hours. The resulting images are stripped down almost to the point of abstraction. Skies become smooth gradients. Water turns into soft planes of tone. Buildings and trees sit as stark silhouettes.

A quiet insight with Kenna is his use of negative space. He is not afraid of leaving most of the frame empty. That emptiness does not feel like a lack. It feels like air and silence. When you see several of his prints together, you realise that the “subject” is often not the tree or the factory, but the space around it.

For anyone who tends to cram their landscapes full of detail, looking at Kenna’s work can be a useful corrective. Try making a photograph where at least half the frame is one simple tone or texture, and see how that changes the mood.

More of Michael Kenna’s work : https://www.michaelkenna.com

6. Max Rive

At the opposite end of the spectrum from minimalist calm, Max Rive is known for epic, high energy mountain landscapes. Based in Europe and travelling widely, he often photographs in very steep, remote terrain that involves serious hiking and sometimes technical routes.

Rive’s images frequently combine dramatic light, huge depth and bold foregrounds. You will see ridgelines catching last light while valleys below sink into shadow, or tiny hikers placed against vast glaciers and peaks.

One niche observation when you study his work is how often the strongest line in the picture is not the horizon, but a diagonal path leading you into the scene. A ridge, a river, a line of rock. That diagonal creates a feeling of movement and travel that fits the adventurous atmosphere.

He also works with weather that many landscape photographers fear: heavy clouds, partial whiteouts, dynamic storms. Instead of waiting only for clear views, he uses holes in the cloud and shifting mist to hide and reveal parts of the scene, which adds a sense of mystery and scale.

More of Max Rive’s work : https://www.maxrivephotography.com

7. Erin Babnik

Erin Babnik is an American landscape photographer particularly associated with dramatic mountain and desert locations, including the Alps and the American Southwest. Her work combines strong compositions with a thoughtful approach to how we represent wild places.

Babnik often builds images around layered depth, using repeating shapes at different scales to pull the eye through. A small foreground rock might echo the shape of a distant peak, or a curve of river might mirror a cloud bank. This visual rhyme gives her work a sense of coherence even when the landscape is complex.

She also writes and teaches about what she calls “expressive landscape photography”: the idea that your images should represent your relationship with a place, not just its postcard appearance. That can mean embracing lens distortion, stitching, focus stacking and other techniques as part of an expressive toolkit rather than treating them as guilty secrets.

A subtle detail in her pictures is how carefully she controls the brightness of the sky. Many of her images have skies that are bright enough to feel open, but not so bright that they pull attention away from the land. That balance can make a huge difference when you print work for the wall.

More of Erin Babnik’s work : https://www.erinbabnik.com

8. Elia Locardi

Elia Locardi is a travel and landscape photographer who has spent large parts of his life effectively living on the road. His portfolio is full of city skylines, coastal scenes and classic viewpoints from across the world, often captured at the most flattering light.

He is particularly associated with a technique some people call “blending moments”, where multiple exposures from the same viewpoint are combined. For example, one frame might capture the deep blue of twilight, another the warm glow of city lights, another the motion of clouds or water. When done well, the result is a single image that condenses a period of time into one seamless view.

A niche insight with Locardi’s work is how carefully he manages small pools of bright colour in night scenes. In many cityscapes, there will be one or two key accents a red sign, a warm lamppost, a lit window that anchor the frame. Without those tiny anchors, the scene could easily dissolve into a blur of lights.

For photographers who enjoy travel and want to make images that feel more like carefully crafted posters than quick snapshots, his work shows what is possible when you combine location research, patient waiting and thoughtful post production.

More of Elia Locardi’s work : https://www.elialocardi.com

9. Nadav Kander

Nadav Kander is widely known for portrait and editorial work, but his landscape projects deserve just as much attention. His series “Yangtze, The Long River” and “Dust” show man made structures in vast, often desolate environments, and sit somewhere between landscape, documentary and fine art.

Kander’s landscapes are not about untouched nature. They are about the uneasy meeting point between human activity and land or water. Cooling towers, half built bridges, isolated monuments. These subjects could easily slide into heavy handed commentary, but Kander treats them with a quiet, measured eye.

One subtle but important aspect of his landscape work is colour temperature. Many images sit in a limited palette of greys, greens and browns, with small, slightly warmer or cooler accents. That restricted palette creates a mood that feels both calm and slightly unsettling, like walking through a place where time has slowed.

If you are used to thinking of landscape photography as purely celebratory, Kander’s work is a reminder that images of nature and place can also be critical, reflective and questioning.

More of Nadav Kander’s work : https://www.nadavkander.com

10. David Noton

David Noton is a British landscape and travel photographer whose work has appeared in books, magazines and advertising for many years. He has photographed widely across the UK and abroad, but often returns to familiar places, working them through changing seasons and light.

Noton’s images balance strong compositions with a very approachable, “this is what you would see if you were here” feel. He uses wide angles without distortion becoming the story, and he is careful to keep detail in both shadows and highlights, so the viewer’s eye can roam without hitting harsh, blocked up areas.

An understated but telling habit in his work is the way he often includes small traces of human presence in otherwise natural scenes: a path, a distant cottage, a trail of light on a distant road. These details give a sense of scale and place, and acknowledge that most landscapes we love are not truly wild, but lived in.

For people starting to collect landscape prints, Noton’s work is a good reference for images that sit comfortably in a living space. They are rich and interesting without shouting for attention.

More of David Noton’s work : https://www.davidnoton.com

How to use this list as a learning tool

You could treat a list like this as something to read once and move on from, but there is a more useful way to work with it.

Pick two photographers whose work seems very different. Perhaps Michael Kenna and Max Rive, or Rachael Talibart and Elia Locardi. Spend ten minutes with each portfolio and ask yourself three questions.

- Where do they stand

Look at vantage point. Are they low to the ground or high? Are they often on ridges, in valleys, at the waterline? You will start to see that each photographer has favourite positions. - How much of the frame is empty

Pay attention to sky, water and shadow. Do they fill the frame with information, or do they leave big areas of simplicity. - How do they use weather

Do they chase big storms, clean blue skies, fog, snow, flat grey? Which weather matches their personality.

Those questions are not about copying anyone. They are about noticing that each landscape photographer slowly builds a vocabulary of choices. Over time, those choices add up to a recognisable voice.

If you make photographs yourself, you can ask the same questions of your own work. It may show you that you already have stronger preferences and patterns than you realised.

Why landscape photography matters

In a world where phone cameras are everywhere and social media feeds are full of mountain views and sunsets, it is easy to wonder whether landscape photography has anything left to say. The ten photographers above suggest that it does.

What they have in common is not a particular style, but a consistent way of paying attention. They return to places. They notice small changes. They respect weather and light. They are willing to come home with nothing if the conditions are wrong, and to stay a little longer when everything suddenly falls into place.

For viewers and collectors, landscape photography offers something that is increasingly rare: a chance to look at the world without scrolling. A print on a wall is not competing with the next image. It lives with you, slowly revealing more over months and years.

For photographers, these artists are reminders that there is room for many voices. You do not have to chase the most dramatic scenes on the planet. Some of the most quietly affecting landscape images are made within an hour of home, by people who know a particular hill, beach or wood in detail.

If this list nudges you to explore one new photographer, revisit a favourite, or simply pay more attention next time you are out in bad weather, it has done its job. Nature’s beauty is not just something to admire at a distance. In the hands of good landscape photographers, it becomes a way of seeing that we can carry back into the rest of life.

Leave a Reply