No products in the cart.

Discovering the Pointillism Movement – Art Created Dot by Dot

The Art of Dots

Emerging in the late 19th century, Pointillism broke away from the traditional brushstroke techniques of Impressionism and instead embraced the precision of tiny, deliberate dots of colour. At first glance, a Pointillist painting might seem like an abstract scatter of colour, but as you step back, those tiny dots come together to form vivid and cohesive images—landscapes, portraits, and scenes teeming with light and life.

Pointillism was born in France, closely aligned with the broader Neo-Impressionist movement, which sought to build upon the principles of Impressionism using more scientific approaches to colour and composition. Rather than blending pigments on a palette, Pointillist artists applied pure colours directly onto the canvas in dots and dashes, relying on the viewer’s eye to mix them optically. This created a shimmering, luminous effect that gave their paintings a distinct visual character.

The movement was pioneered by artists like Georges Seurat and Paul Signac, who believed that this method of separating colours would produce greater brilliance and harmony. Over time, Pointillism became more than just a technique—it was a philosophy of seeing, one that transformed the act of painting into a study of perception, patience, and precision.

The Birth of Pointillism: Seurat and Signac

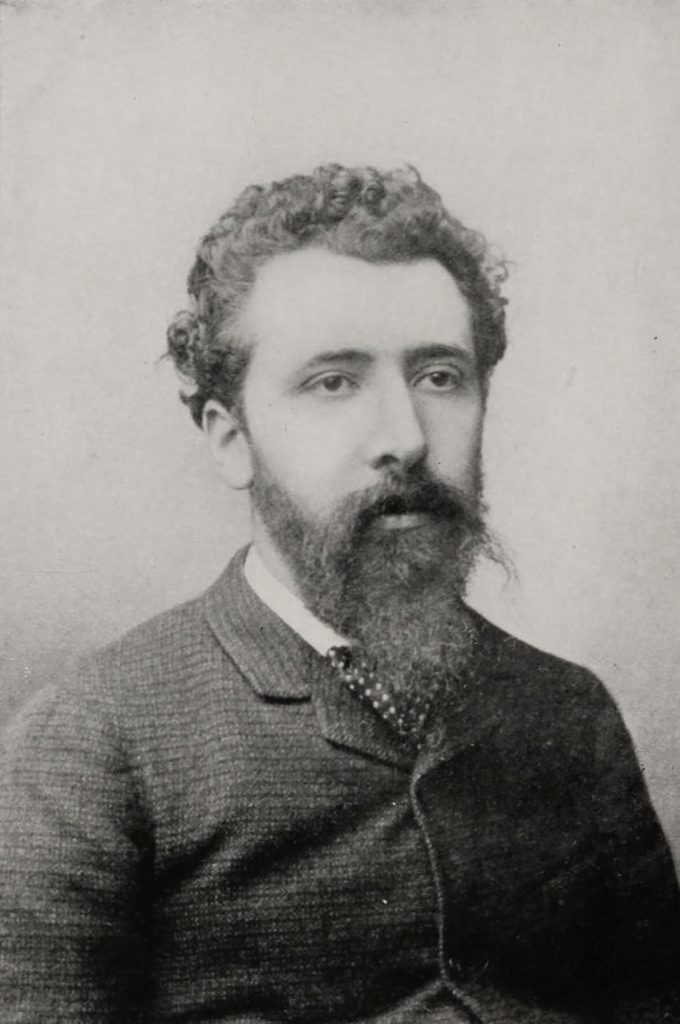

The roots of Pointillism lie in the fertile ground of late 19th-century Paris, where a wave of new thinking was redefining the boundaries of visual art. At the centre of this revolution was Georges Seurat, a young French painter whose meticulous, analytical approach to colour and form led to the development of a brand-new technique. Instead of blending colours on a palette or using loose brushstrokes like the Impressionists, Seurat placed tiny, individual dots of pure colour directly onto the canvas. His most iconic work, A Sunday Afternoon on the Island of La Grande Jatte, completed in 1886, stands as the definitive example of the style. When viewed up close, it appears almost abstract. But from a distance, it transforms into a luminous, detailed scene of Parisians relaxing along the banks of the River Seine.

Seurat was not working in isolation. Around the same time, fellow artist Paul Signac embraced and expanded the technique, becoming one of Pointillism’s most dedicated proponents. The two worked closely, and Signac would go on to champion the method even after Seurat’s early death in 1891. Signac’s paintings—often of sunlit harbours, sailboats, and coastal towns—embraced Pointillism with more freedom and colour variation, pushing the style beyond Seurat’s original restraint.

Interestingly, the term “Pointillism” was originally coined by art critics as a jab. It was used dismissively, suggesting that the style was mechanical or overly academic. But artists like Signac reclaimed the term, and over time, it lost its negative connotations and became the accepted name of a major movement. This shift speaks volumes about how new ideas in art often face resistance before being recognised for their innovation.

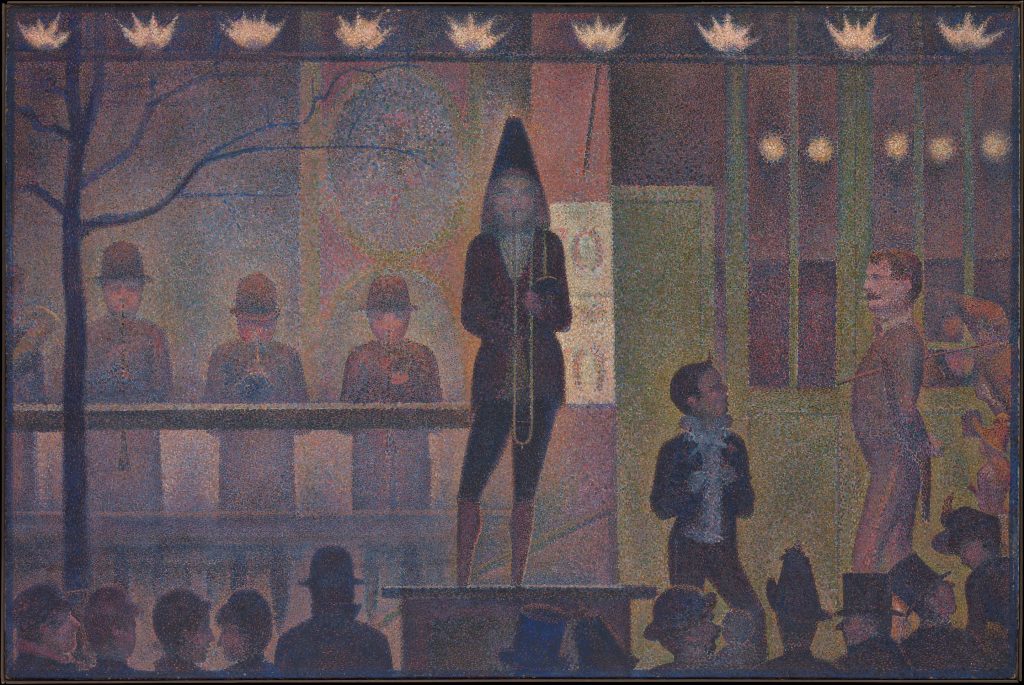

Georges Seurat 1887-88

Scientific Foundations: Colour Theory and Optical Mixing

What made Pointillism more than just a stylistic curiosity was its grounding in science—specifically, in colour theory and optical perception. Seurat was greatly influenced by contemporary scientific research, particularly the work of French chemist Michel Eugène Chevreul. Chevreul’s theories on simultaneous contrast—the idea that the perception of one colour is affected by the colours surrounding it—inspired Seurat to experiment with how the eye blends colours naturally, without physical mixing on the canvas.

Rather than mixing pigments into muddy shades, Pointillist artists would apply small, unblended dots of pure colour side by side. The viewer’s eye, at a certain distance, would fuse these points together. For example, blue and yellow dots placed close together would appear as green to the eye, creating a shimmering, light-filled effect that conventional brushwork couldn’t match.

This technique, known as optical mixing, gave Pointillist works a brightness and clarity that set them apart. The meticulous application of thousands upon thousands of tiny dots demanded both technical skill and enormous patience. But the result was something completely new—paintings that seemed to vibrate with light and movement, all created through the science of seeing.

Notable Pointillist Artists and Their Works

Georges Seurat

Georges Seurat is considered the pioneer of Pointillism, having developed the technique in the 1880s as part of the broader Neo-Impressionist movement. Trained in classical methods but deeply influenced by scientific theories of colour and optics, Seurat began to experiment with a method he called “chromoluminarism”—a systematic application of tiny dots of pure colour that, when viewed from a distance, visually blend into a luminous whole.

His most famous painting, A Sunday Afternoon on the Island of La Grande Jatte (1884–1886), is the movement’s defining masterpiece. Painted on a large canvas using oil paint, the work captures Parisians relaxing by the Seine and exemplifies the precision and patience required for the Pointillist technique. Another important work, Bathers at Asnières (1884), marks an earlier phase in his experimentation and demonstrates the transition from traditional brushwork to his dot-based method.

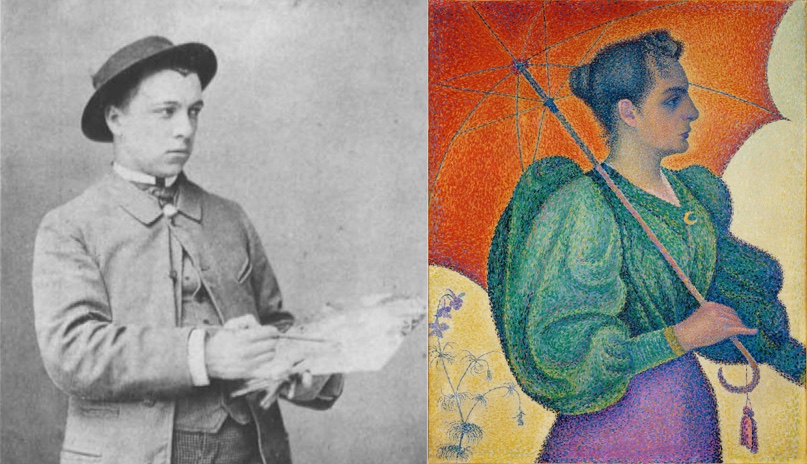

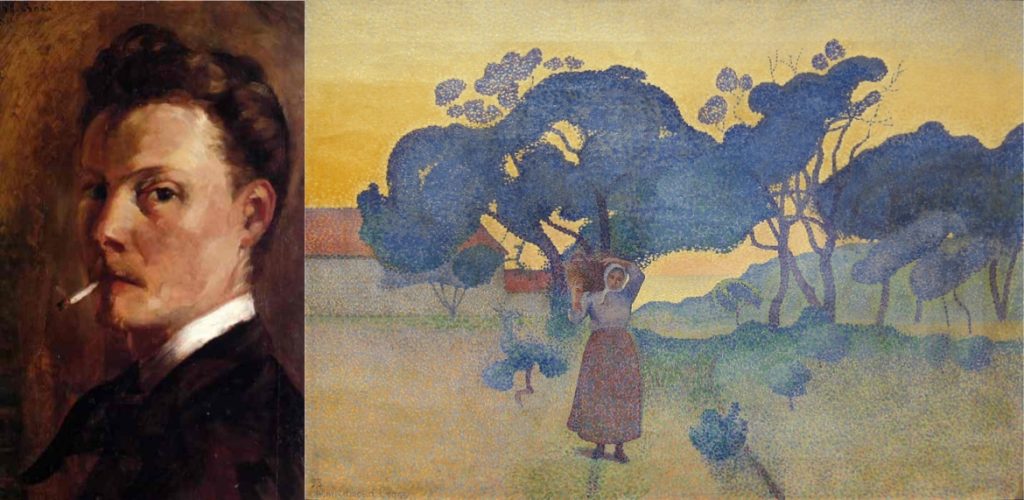

Paul Signac

Paul Signac was not only Seurat’s close collaborator but also a driving force in the continuation and evolution of Pointillism after Seurat’s death. Initially inspired by Impressionism, Signac fully embraced the Pointillist method and became one of its most vocal champions. He preferred watercolours and oils on canvas, using short, evenly spaced dots and strokes to construct vivid seascapes, city scenes, and landscapes.

One of his most celebrated works, The Port of Saint-Tropez (1901–1902), exemplifies how he captured light and atmosphere through pure colour and a careful dot technique. Another key piece, The Pine Tree at Saint-Tropez, uses the method to dramatise natural forms with radiant hues. Signac was also a theorist, and his book From Eugène Delacroix to Neo-Impressionism (1899) helped define and disseminate the principles of the movement.

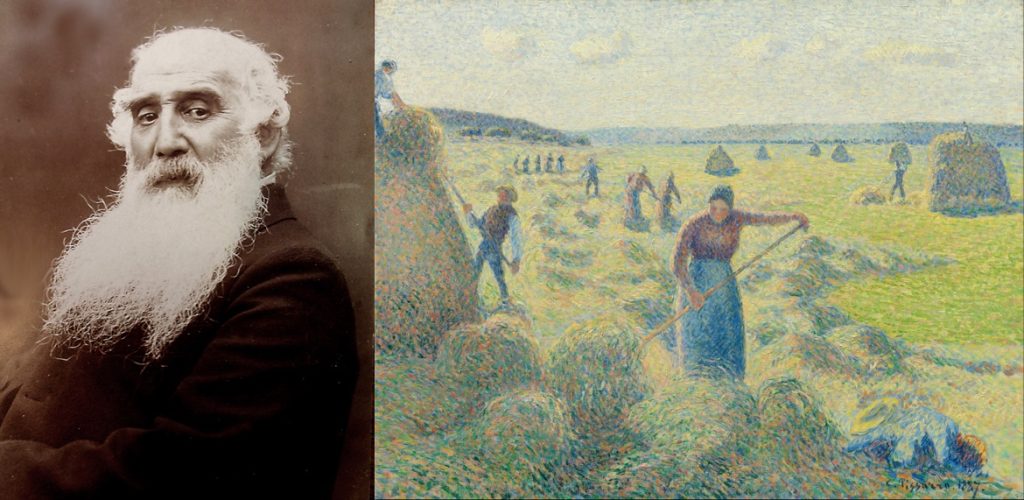

Camille Pissarro

Though originally an Impressionist, Camille Pissarro became interested in Pointillism in the 1880s, adopting the style briefly in collaboration with Seurat and Signac. Pissarro’s interpretation of the technique was slightly looser, often blending the dot method with soft brushwork. He applied Pointillism to everyday scenes, particularly those portraying rural and agricultural life.

Works such as Peasant Girl Drinking Her Coffee and The Garden of Pontoise display his Pointillist phase, where he used fine, coloured dots to enrich the light and texture of his subjects. Unlike Seurat and Signac, Pissarro eventually returned to his earlier, more spontaneous Impressionist style but left behind several important Pointillist works.

Henri-Edmond Cross

Henri-Edmond Cross was a key figure in the second wave of Neo-Impressionism and brought a softer, more decorative sensibility to Pointillism. Using slightly larger, mosaic-like strokes rather than tiny dots, Cross developed a more painterly variation of the technique. His work had a significant influence on later movements, particularly Fauvism.

Notable paintings such as The Pink Cloud (1896) and The Evening Air reflect his vibrant use of colour and light. These works often depict Mediterranean landscapes and aim to capture a dreamlike atmosphere, using Pointillist principles to heighten their emotional and aesthetic effect.

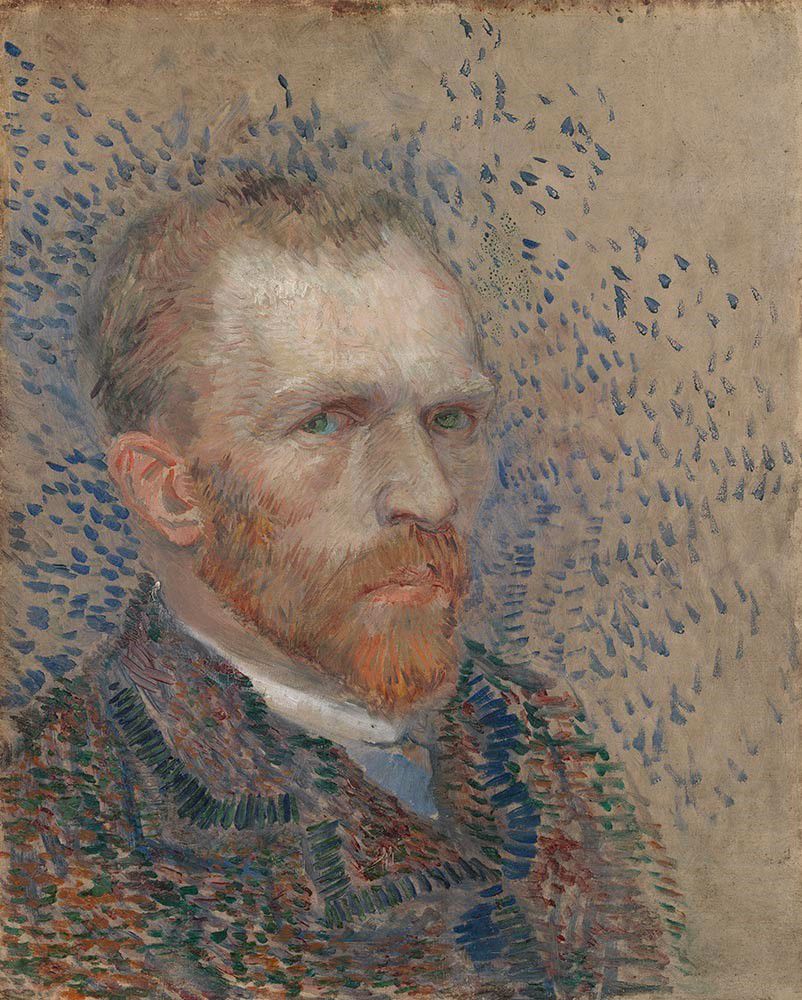

Vincent van Gogh

Vincent van Gogh experimented with Pointillist techniques during his time in Paris (1886–1888), where he encountered the works of Seurat and Signac. Though he never fully embraced the style, van Gogh was inspired by its colour theories and incorporated aspects of the method into his own evolving approach.

In paintings like Self-Portrait with a Straw Hat and The Seine with the Pont de la Grande Jette, he used small, repetitive strokes and dots of complementary colours to intensify vibrancy and texture. Rather than following the rigid structure of Pointillism, van Gogh adapted its techniques to suit his more expressive and emotive style.

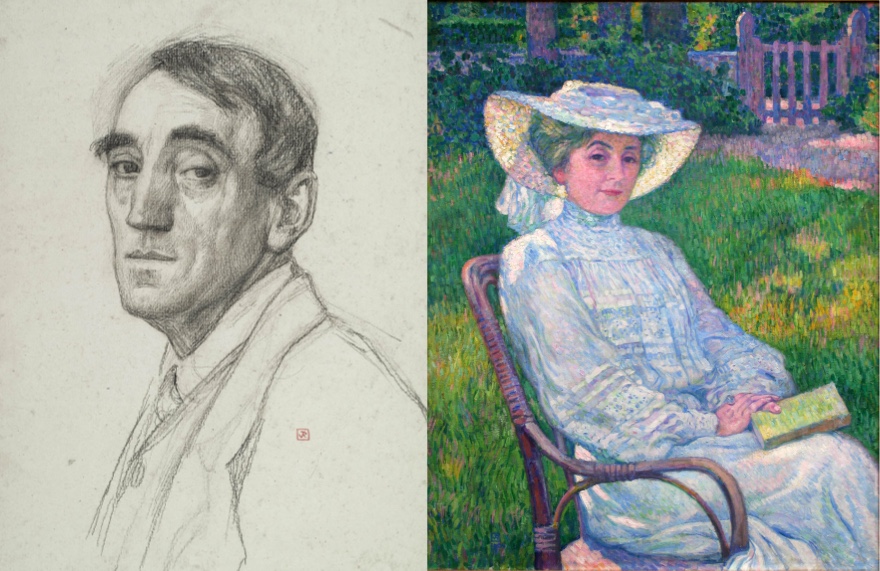

Théo van Rysselberghe

Théo van Rysselberghe was a Belgian Neo-Impressionist who applied Pointillism particularly in portraiture. His Portrait of Irma Sèthe (1894) is one of the finest examples of the technique used in a figurative context. Using hundreds of delicate colour dots, van Rysselberghe captured the subtle lighting and emotional tone of the subject, a violinist lost in concentration.

He successfully combined the scientific approach of Pointillism with the warmth and intimacy of traditional portrait painting. His broader body of work includes seascapes and domestic interiors, all benefiting from his skill in balancing technical discipline with artistic nuance.

Pointillism’s Influence on Modern Art

Pointillism, while relatively short-lived as a formal movement, cast a long shadow across the evolution of modern art. Emerging at the end of the 19th century as a highly systematic method of painting rooted in colour theory and science, its legacy can be traced through several major 20th-century art movements. From Fauvism to Cubism and even into contemporary digital art, the echoes of Pointillism remain present in the ways artists approach colour, structure, and composition.

From Dots to Bold Strokes: The Influence on Fauvism

One of the most direct successors of Pointillism was Fauvism—a movement characterised by its vibrant, non-naturalistic use of colour and expressive brushwork. Henri Matisse, widely regarded as the leader of the Fauves, was directly influenced by the Pointillists during his formative years as an artist. In particular, his exposure to the works of Paul Signac and Henri-Edmond Cross in the south of France during the 1890s made a significant impact on his understanding of colour and its emotional potential.

While Fauvist painters abandoned the strict scientific dotting method of Seurat and Signac, they retained the principle of using pure, unmixed colours placed side by side to achieve luminosity. This technique, rooted in Pointillist practice, allowed them to break away from naturalistic depiction and move towards abstraction and emotional expression. Matisse’s early works, such as Luxe, Calme et Volupté (1904), showcase this transition clearly—its colour fields composed of short, visible strokes inspired by Pointillism, yet moving toward the freer style that would define Fauvism.

Analytical Foundations: From Pointillism to Cubism

Pointillism also played an unexpected role in laying the groundwork for Cubism. While Cubism is generally associated with form, geometry, and structure rather than colour, artists like Georges Braque and Pablo Picasso were deeply engaged in the analytical breakdown of subjects. The conceptual approach taken by Seurat—where an image is not just painted but constructed through methodical elements—shares an intellectual affinity with the Cubist desire to deconstruct and reassemble reality.

The idea that a painting could be approached like a visual equation, built through discrete units (dots in the case of Pointillism, facets in Cubism), marked a turning point in modernist thinking. Seurat’s meticulous attention to composition, structure, and rhythm inspired a generation of artists to think about painting as a system, not just a representation.

Beyond the Canvas: The Digital Legacy of Pointillism

In contemporary art, the principles of Pointillism have been extended and reimagined through digital tools. The concept of image creation via the accumulation of tiny units finds a direct analogue in pixel-based art, a hallmark of digital and graphic design. Just as Seurat placed dots of paint to build a cohesive image from a distance, digital artists use pixels to achieve clarity and complexity on screen.

Moreover, contemporary painters continue to experiment with the optical effects pioneered by Pointillism. Some use small repeated patterns or modular elements to create texture and depth, drawing on the same principles of optical mixing and colour contrast. Others, particularly those working in installation or light-based art, use digital projections or LED grids to simulate Pointillist dynamics in new media.

The philosophy behind Pointillism—that the eye, not the brush, completes the image—remains a powerful concept in 21st-century art, especially in work that blurs the line between analogue and digital.

A Legacy of Precision and Colour

Ultimately, Pointillism’s most lasting contribution to modern art lies in its disciplined exploration of how colour and perception interact. It encouraged artists to approach painting as both science and poetry, and to seek out new ways of engaging the viewer’s eye. Movements like Fauvism celebrated its colour innovations, Cubism expanded on its structural logic, and contemporary artists continue to draw on its spirit of experimentation.

Pointillism may have been defined by its dots, but its impact radiated far beyond them—changing not just how artists paint, but how audiences see.

Experiencing Pointillism Today

Pointillism is far more than an art historical term—it’s a visual experience that continues to captivate viewers in galleries across the world. Whether you’re encountering these vibrant dot-based masterpieces for the first time or revisiting them with a more trained eye, seeing them in person offers a special kind of magic.

Some of the most iconic Pointillist works are housed in world-renowned institutions. Georges Seurat’s A Sunday Afternoon on the Island of La Grande Jatte, arguably the movement’s most famous painting, is on permanent display at the Art Institute of Chicago. Meanwhile, the Museum of Modern Art in New York (MoMA) holds several works by Paul Signac and his contemporaries, offering a glimpse into the evolution of Pointillism and its links with later modern art.

If international travel isn’t on your itinerary, many museums now offer exceptional virtual experiences. Online collections hosted by institutions like The Met, MoMA, and the Musée d’Orsay allow users to zoom in on high-resolution images of Pointillist works. This provides a close-up view of the painstaking dot-by-dot technique used by these artists—something that’s difficult to fully grasp in person unless you’re standing inches from the canvas.

When viewing Pointillist paintings—whether on screen or in a gallery—it’s worth stepping back and forth. Up close, you’ll see the tiny, deliberate dots of pure colour. But as you move further away, your eyes blend the colours together, revealing a seamless image. This play between proximity and distance is what makes Pointillism so unique. It’s not just a style—it’s an optical performance.

Here’s a curated list of major galleries and museums across the UK and Europe where you can experience Pointillism first-hand. These institutions either house original works by artists like Georges Seurat, Paul Signac, Camille Pissarro, and others, or feature them in rotating exhibitions and online collections.

1. The National Gallery – London, UK

Home to works by Camille Pissarro and other Post-Impressionists. While it doesn’t own Seurat’s La Grande Jatte, the collection offers excellent context around the movement.

Website: https://www.nationalgallery.org.uk

2. The Courtauld Gallery – London, UK

The Courtauld houses significant works by Seurat and his contemporaries, including The Bridge at Courbevoie, and regularly explores Neo-Impressionism.

Website: https://courtauld.ac.uk/gallery/

3. Musée d’Orsay – Paris, France

One of the richest collections of Pointillist and Post-Impressionist work in the world. See Seurat, Signac, Cross, and others in their full, vibrant glory.

Website: https://www.musee-orsay.fr/en

4. Musée d’Art Moderne de Paris – Paris, France

Holds a strong collection of works by Paul Signac and Henri-Edmond Cross, especially in their later careers bridging into Fauvism.

Website: https://www.mam.paris.fr/en

5. Kröller-Müller Museum – Otterlo, Netherlands

This museum boasts one of the largest Van Gogh collections and includes works showing his brief experimentation with Pointillist techniques.

Website: https://krollermuller.nl/en

6. Van Gogh Museum – Amsterdam, Netherlands

Alongside his iconic works, you can view early Paris-period pieces where Van Gogh experimented with Pointillist brushstrokes and colour harmony.

Website: https://www.vangoghmuseum.nl/en

7. Kunstmuseum Basel – Basel, Switzerland

Features works by Théo van Rysselberghe and other European artists influenced by Pointillism and Neo-Impressionism.

Website: https://kunstmuseumbasel.ch/en

8. Royal Museums of Fine Arts of Belgium – Brussels, Belgium

Includes pieces by Théo van Rysselberghe and others who adapted Pointillist technique into portraiture and Belgian art circles.

Website: https://www.fine-arts-museum.be/en

9. Museum Folkwang – Essen, Germany

A renowned collection of 19th and 20th-century art, including Pointillist and Post-Impressionist paintings with deep curatorial context.

Website: https://www.museum-folkwang.de/en.html

The Enduring Charm of Pointillism

Pointillism may have been born in the 19th century, but its relevance and beauty are timeless. What began as a radical experiment in technique and colour theory has grown into one of the most celebrated approaches in the history of modern art.

The dedication of artists like Georges Seurat, Paul Signac, Camille Pissarro, and Henri-Edmond Cross brought a scientific sensibility to painting, blending aesthetics with optics to stunning effect. The legacy of their work echoes through the bold hues of Fauvism, the geometric analyses of Cubism, and even the vibrant compositions of contemporary digital artists today.

Whether viewed up close for their technical mastery or admired from afar for their dreamy cohesion, Pointillist works invite us to slow down and truly look. They challenge our perception and reward our attention—offering not just beauty, but insight into how we see the world.

So next time you’re in a gallery or browsing an online collection, take a moment to linger on the dots. There’s a whole universe hidden in them—patiently waiting to be seen.

Let me know if you’d like a short meta description or social preview text for this blog too.

Leave a Reply