No products in the cart.

What Is a Triptych? History, Meaning, and Modern Usage in Art

A triptych is a form of art composed of three distinct panels, traditionally hinged so that they could open and close like a book. In more recent times, these three components are often positioned side by side, to be viewed either as one cohesive piece or as three interrelated images. This setup frequently serves as a visual narrative—offering a beginning, middle, and end—or it can be used to present multiple angles on a unifying theme.

The term “triptych” originates from the Greek word triptychos, which translates to “three-fold.” This nod to folding highlights the triptych’s roots in religious art, particularly portable altarpieces in which the central panel was complemented by two side wings. Yet the triple-panel arrangement is more than a practical design choice. In Christian art, it resonates with the concept of the Holy Trinity, while in storytelling, it provides a rhythm and balance that many find intuitively satisfying. Visually, a striking central panel framed by two accompanying images can achieve a sense of harmony, offering both symmetry and the opportunity for contrast.

What Is a Triptych?

A triptych is a work of art designed in three segments, generally arranged side by side to create a unified whole. Historically, these three segments—often referred to as panels—were hinged, enabling them to fold inwards for protection or ease of travel. In more modern renditions, the panels simply hang in a row, but the concept remains the same: each of the three parts contributes to one overarching theme or story.

While triptychs have roots tracing back to the Middle Ages, when religious altarpieces commonly featured hinged wings, this three-panel format has proven remarkably adaptable over time. Today, artists in a variety of disciplines—including painting, photography, and mixed-media—continue to employ the triptych to present layered narratives or complementary perspectives within a single artwork. Often, the centre panel carries the main subject, with the left and right panels providing contextual details or contrasting imagery.

For an in-person experience of this format, one might visit a local art museum or a prominent institution such as the National Gallery in London, which often displays historical as well as contemporary triptych pieces. Observing these three-part works firsthand offers a closer look at how the format can enhance storytelling, evoke symbolic resonance, or heighten visual impact.

Medieval Foundations: Faith, Symbolism, and the Middle Ages

The Early Rise of Triptychs in Medieval Worship

Triptychs first emerged as prominent altar pieces during the Middle Ages. In many European churches, these three-panel artworks were placed behind the altar, serving as visual aids to religious devotion. The central panel often depicted a major biblical scene—such as the Crucifixion or the Virgin and Child—while the flanking “wings” featured supporting figures or events that enriched the overall narrative. This format quickly gained popularity, both for its aesthetic appeal and its capacity to convey intricate theological stories to congregations that were largely illiterate.

Hinging and Narrative Power

A key characteristic of medieval triptychs was the use of hinges, enabling the side panels to fold inward and protect the central painting. When opened, the triptych effectively operated like a storybook, unveiling elaborate biblical narratives across three distinct scenes. This unfolding effect heightened the viewer’s sense of participation: worshippers could experience the drama of scripture in a structured, almost theatrical presentation.

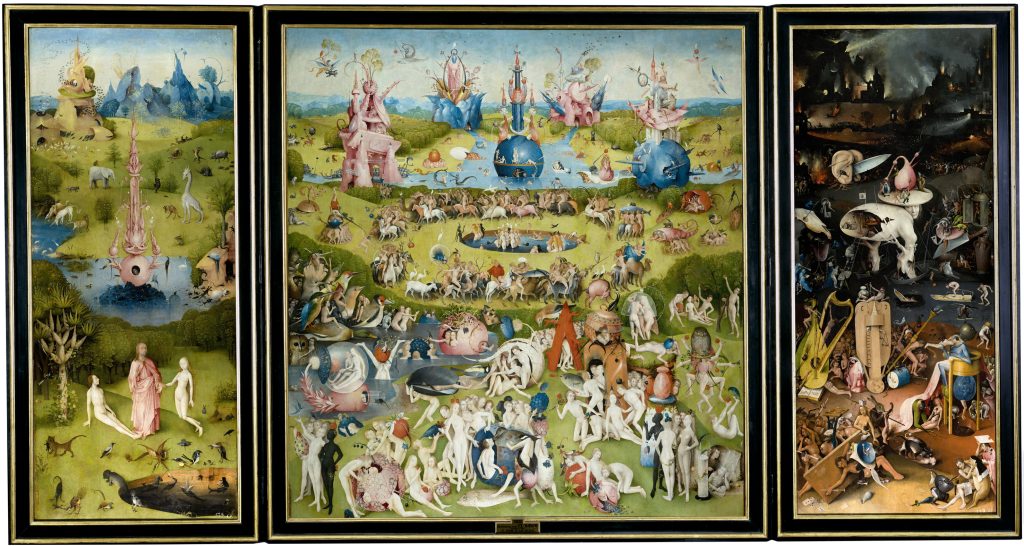

Iconic Example: Hieronymus Bosch’s The Garden of Earthly Delights

Among the most famous late-medieval-to-Renaissance triptychs is The Garden of Earthly Delights, created by Hieronymus Bosch around 1490–1510. In this work, the left panel portrays the Garden of Eden, the centre panel brims with chaotic depictions of worldly pleasures, and the right panel offers a haunting vision of Hell. Together, these three views form a moral narrative that spans innocence, temptation, and dire consequence. To witness this piece firsthand, visitors can explore it at the Museo del Prado in Madrid and see how Bosch arranged each panel to create a powerful, interlinked narrative.

Why Three Panels?

The prevalence of three panels in medieval religious art is partly attributed to the Holy Trinity—representing Father, Son, and Holy Spirit—reflecting the core of Christian doctrine. Equally, the notion of a three-part structure resonates with the universal idea of a beginning, middle, and end. Just as stories often unfold in three acts, medieval altarpieces used triptychs to guide viewers through distinct phases of sacred history. These hinged paintings were thus uniquely suited to convey spiritual teachings, leaving a lasting impact that continues to shape the ways artists compose multi-panel works today.

Renaissance and the 19th Century: From Devotion to Drama

Transition to New Eras

During the Renaissance, the triptych format continued to flourish, albeit with broader thematic scope. Artists such as Hans Memling and Sandro Botticelli employed multi-panel works for both religious commissions and more secular storytelling. While many triptychs of this era still featured biblical narratives, there was an increasing shift toward scenes of mythological or historical interest, reflecting the Renaissance fascination with humanism and classical antiquity.

Art Movements Evolve

As Europe moved beyond the Renaissance, panel painting gradually diversified. Baroque, Rococo, and Neoclassical styles introduced new emphasis on single-canvas history paintings or large frescoes, which temporarily lessened the visibility of the triptych format in mainstream church commissions. However, the idea of partitioning a composition into three balanced parts never fully disappeared. Painters occasionally chose this structure for private altarpieces or for patrons seeking a traditional layout with updated subject matter.

19th Century Fascination

By the 19th century, periods of Romanticism and early modernism renewed interest in medieval and Renaissance art forms. Some artists—though fewer than in previous centuries—explored the multi-panel concept as a way of telling elaborate stories that might otherwise sprawl across several canvases. This was especially appealing to those drawn to historical or literary subjects who found the triptych format adaptable for narrative arcs and symbolic juxtapositions.

For a closer look at Renaissance triptychs and related artworks, consider visiting the Uffizi Gallery online collection. This digital resource offers a window into how multi-panel paintings evolved during one of Europe’s most innovative artistic periods.

The Symbolic Power of Three

Balance & Harmony

One of the most compelling aspects of the triptych format is its innate sense of equilibrium. By placing a central focal panel between two complementary wings, artists can achieve visual balance without relying on strict symmetry. This design often creates a steady rhythm for the viewer’s eye, guiding it inward towards the centre panel or outward to the supporting sides. It’s a layout that can accommodate a wide range of compositions—from serene landscapes to dramatic figurative scenes—while retaining a cohesive look. For an in-person demonstration of this principle, you might explore relevant exhibitions at the National Gallery, where historical triptychs are often curated to highlight their balanced structure.

Narrative Flow

Beyond the visual appeal, the triptych format allows for a natural narrative progression. Much like reading a book, a viewer may start with the left panel, move through the centre “climax,” and conclude with the right panel’s resolution or contrasting viewpoint. This sequential aspect can be especially evident in religious or mythological artworks, where each panel depicts a separate phase of a grand story. Even in modern or abstract pieces, the three-part design subtly encourages the audience to look for connections or a developmental arc across the panels. At times, artists might use linear transitions—such as colour shifts or stylistic changes—to reinforce the sense of a beginning, middle, and end within the same artwork.

Unity & Contrast

Although each panel can stand on its own, the true strength of a triptych lies in the dynamic between the sections. The centre panel often holds the main theme or subject, while the two outer panels may offer parallel narratives, background detail, or even deliberate contradictions. This interplay can heighten tension, add surprise, or deepen thematic resonance. Consider the way some painters feature a bold central motif surrounded by gentler side images—a device that amplifies the impact of the middle panel. In other cases, the panels might be nearly identical in colour or design, creating a sense of harmony and reinforcing the unity of the entire piece. To see this principle in action, one might look at examples of panel painting in the Uffizi Gallery’s online collection, where multi-panel works demonstrate both synchronised and contrasting panels.

Personal Reflection

Encountering a triptych in a gallery can feel immersive, offering a multi-layered perspective that a single canvas might not provide. There is often a sense of stepping into a narrative space: each panel reveals its own moment or facet of a story, yet all three remain connected by visual cues like shared colour palettes or compositional lines. Viewers may find themselves drawn to move closer, step back, and compare details across panels, engaging with the artwork on multiple levels. This active participation can foster a deeper emotional response—one that might be profound in religious settings or intriguingly open-ended in contemporary art. Whether exploring medieval icons or modern abstract creations, the triptych’s threefold design continues to captivate, inviting audiences to pause, reflect, and perhaps discover unexpected insights along the way.

Modern and Twentieth Century Rebirth: Matisse, Kandinsky, Bacon, and More

Fresh Eyes on an Old Format

As the art world transitioned into the early twentieth century, a wave of modern artists revisited the triptych concept, drawn by its potential to break free from single-canvas conventions. While the format had long been associated with religious altarpieces, these innovators discovered that three panels could also serve secular, abstract, and deeply personal expressions. By adopting—or adapting—the triptych structure, they found new ways to compartmentalise themes, experiment with spatial dynamics, and engage viewers on multiple visual and emotional levels.

Henri Matisse: Bridging Tradition and Modernism

Famed for his bold use of colour and fluid line work, Henri Matisse embodied the transition from traditional painting methods to a vibrant, modern aesthetic. While Matisse did not exclusively rely on triptychs, he occasionally worked in large-scale decorative panels where each section built upon the others in a unified design. This multi-panel approach allowed him to explore an expansive canvas in a segmented manner—one that echoed medieval precedents but placed them firmly within the realm of modernism. Such works exemplify how artists like Matisse could pay subtle homage to Middle Ages formats while forging new avenues for creativity. To learn more about modern art’s evolution, one might explore the collection at the Centre Pompidou.

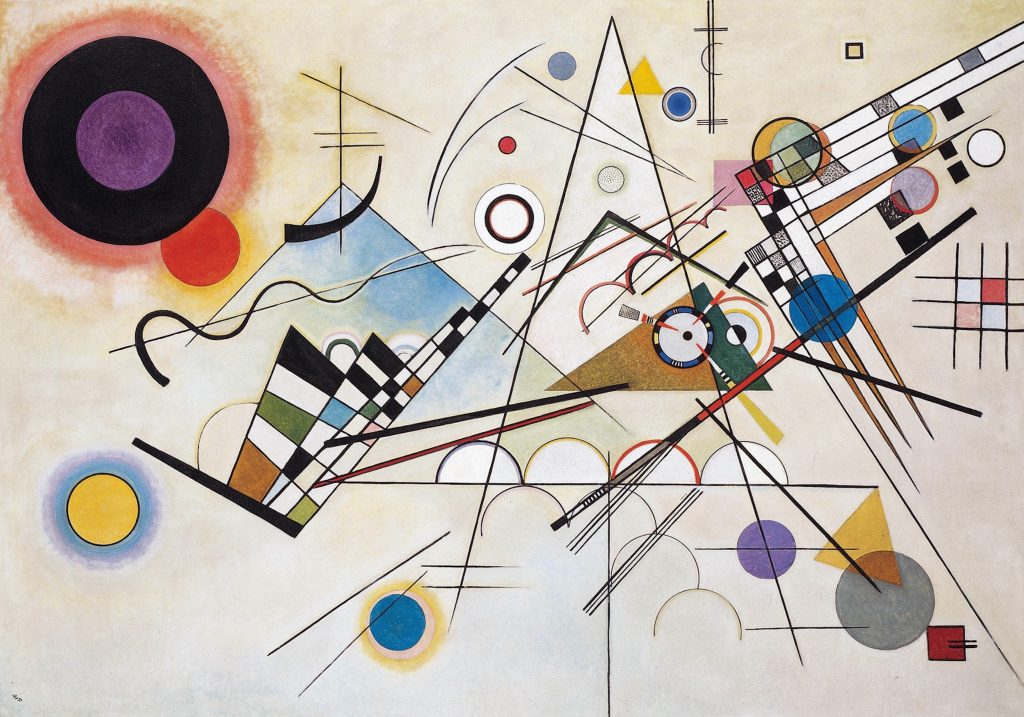

Wassily Kandinsky: The Abstract Appeal of Division

Wassily Kandinsky, a pioneer of abstract painting, also demonstrated an interest in multi-panel configurations. Though much of his work is known for single-canvas compositions, Kandinsky at times arranged related pieces in sequences that conveyed shifting moods or colour harmonies. These loose, multi-part series showed that the principle of dividing an artwork into sections—whether strictly a triptych or otherwise—could align with modern abstraction’s emphasis on movement, variation, and non-representational storytelling. Kandinsky’s approach underscores how dividing space can enhance the rhythmic or thematic continuity of an artwork.

Francis Bacon: Edgy, Psychological Triptychs

Few twentieth-century painters harnessed the raw potential of triptychs as powerfully as Francis Bacon. His edgy, emotionally charged works—such as Three Studies for Figures at the Base of a Crucifixion (1944)—brought an intense, secular energy to a format that had once been reserved for altarpieces. Bacon’s triptychs often spotlighted twisted, tormented figures spread across three panels, each variation on a central theme. This arrangement let him explore psychological tension in a layered, almost cinematic fashion. Those interested in viewing Bacon’s triptychs firsthand can find notable examples at Tate Britain, where the interplay of the three canvases delivers a striking emotional impact.

Picasso and the Pop Art Connection

While Pablo Picasso was more inclined to deconstruct perspective than to craft formal triptychs, his multi-perspective approach had parallels with the concept of dividing a subject into segments. The idea of examining one theme from different angles resonates with the triptych’s capacity for presenting related views in a single overarching piece. Later, Pop Art figures such as Andy Warhol pushed the notion of repeated imagery to new heights, often displaying rows or grids of the same portrait. Although many Pop Art works are not strictly triptychs, the principle of using repeated or partitioned visuals to create a grander statement recalls the underlying appeal of three-panel design.

By adapting older methods to fit modern sensibilities, these twentieth-century luminaries revealed just how versatile the triptych format could be. Whether used to delve into psychological intensity, bold colour harmonies, or fresh perspectives on everyday images, the basic structure of three panels continued to offer an enduring canvas for artistic innovation.

Contemporary Artists and the Triptych Format

Panel Painting in Modern and Contemporary Art

Contemporary artists continue to embrace the triptych as a dynamic way to explore multiple facets of a single theme. Whether large-scale acrylics or mixed-media collage, a three-part layout can frame political commentary, abstract forms, or even personal memoir. By dividing their work into three sections, painters may highlight the progression of a story, compare disparate elements, or create a sense of tension between panels. To discover a range of such modern interpretations, you might examine exhibitions at the Museum of Modern Art in New York, where a variety of multi-panel works often appear in rotation.

Expanding Boundaries: Performance and Installation

The notion of a three-act format isn’t confined to canvas. In the realm of performance art and immersive installations, creators sometimes adopt a triptych-like structure by splitting an event or environment into three distinct experiences. One room could present the initial “scene,” the next a pivotal climax, and the third a reflective conclusion—mirroring the way a classic triptych moves a viewer through related imagery. If you’re interested in examples of experimental layouts, consider exploring resources on the Guggenheim Museum website, which often highlights avant-garde projects that push artistic boundaries.

Pop Art Influence: Multi-Panel Repetition

Although Pop Art luminaries such as Andy Warhol famously worked with repeated images—often in diptych or grid-like formats—the principle of breaking an image into multiple segments aligns well with the triptych concept. By replicating celebrity portraits or iconic consumer goods, Warhol and others underscored subtle variations in colour and mood. While not strictly hinged panels, these repeated visuals capture the core idea of seeing one subject from multiple perspectives. Visitors to the Tate’s Pop Art exhibits can see how repetition and segmentation in Warhol’s work echo the underlying appeal that has long powered three-panel designs.

Seeing It in Person: Modern Galleries and Exhibits

For anyone keen to experience contemporary triptychs in a physical space, modern galleries frequently include three-panel works that tackle diverse themes—ranging from social issues to purely abstract explorations. Some shows may even feature interactive or digital triptychs, inviting viewers to engage with separate yet interconnected videos or screens. Institutions like the Saatchi Gallery in London regularly showcase cutting-edge installations, where multi-panel arrangements harness the inherent drama of the triptych format. Whether studying a painting series on climate change or strolling through a triptych-based installation, the opportunity to move between panels in real space remains a compelling aspect of this centuries-old approach to visual storytelling.

Why It All Matters: Understanding the Lasting Appeal

Narrative Depth

One of the most compelling reasons the triptych has endured across centuries is its ability to guide viewers through a structured mini-journey. By presenting a central scene flanked by two related panels, artists can design a self-contained narrative arc—complete with a beginning, middle, and end. This format draws the audience in, prompting a closer look at each panel’s contribution and sparking curiosity about how they interconnect. In this sense, the triptych becomes an active story, encouraging deeper engagement and interpretation than a single image might allow.

Cultural Continuity

From the middle ages altarpieces that first popularised the three-panel layout, through the 19th-century revivals and on into the twentieth century’s modernism, triptychs have shown a remarkable resilience. While each era has adapted the format to its own themes—be it religious devotion, romantic narrative, political commentary, or abstract expression—the underlying framework remains vibrant. This cultural continuity highlights an enduring human fascination with tripartite storytelling, affirming that certain ideas in art transcend the boundaries of time and style.

Emotional Resonance

Whether it is Hieronymus Bosch deploying surreal imagery in The Garden of Earthly Delights or Francis Bacon capturing psychological intensity in three canvases, the triptych format allows for powerful emotional undertones. By splitting a concept into distinct panels, artists can contrast fear and hope, beauty and chaos, or any other dichotomies they wish to explore. Bosch’s left-to-right progression from innocence to sin to retribution epitomises the moral narrative one can achieve in three parts. To appreciate it firsthand, visitors can view The Garden of Earthly Delights at the Museo del Prado in Madrid, a striking demonstration of the triptych’s capacity to immerse viewers in moral and symbolic complexity. Meanwhile, Bacon’s wrenching portraits, seen at Tate Britain, reveal how the same structure can probe personal trauma and existential angst.

Art World Relevance

Far from being a historical curiosity, triptychs remain a staple in major exhibitions, auctions, and private collections. Contemporary painters, photographers, and mixed-media artists continue to find fresh approaches to this threefold arrangement—whether by dissecting modern social issues, pushing abstract forms, or experimenting with technology-driven installations. The enduring market for triptychs in high-profile auction houses further testifies to their ongoing significance. In galleries and museums worldwide, curators often spotlight multi-panel works to show how classical traditions can morph into cutting-edge expressions of current artistic concerns.

For art enthusiasts, spotting a triptych on their next museum visit offers a unique lens into both historical continuity and artistic innovation. Observing how each panel complements the others can be a revealing experience: subtle details in one section might alter one’s reading of the scene as a whole, prompting repeated glances and a richer aesthetic engagement. In many respects, the triptych represents the perfect blend of tradition, narrative storytelling, and contemporary creativity. By pausing to study all three panels—and the spaces between them—viewers can uncover a wealth of meaning hidden within this enduring format, whether it’s a centuries-old altarpiece or a sleek, modern reinterpretation.

Reflective Note

Encountering a triptych can significantly reshape how we engage with art. Instead of taking in a single frame all at once, viewers are invited to journey from panel to panel, comparing details and piecing together a story. Whether that narrative is religious, historical, psychological, or purely abstract, the triptych format capitalises on the number three’s natural rhythm—beginning, middle, end—to heighten emotional or thematic impact.

For those intrigued, exploring triptychs in person or online is a rewarding next step. Consider visiting a nearby museum’s gallery or delving into digital resources to learn more about how modern and contemporary art expansions on the triple-panel concept continue to push boundaries. For example, you might consult an online catalogue of performance art projects at: https://www.moma.org/. Here, you will find works that, while not always presented as physical triptychs, often employ the same principle of a three-act structure to immerse viewers.

Whether you are a casual observer or an aspiring artist, experimenting with the triptych format—on canvas, in photography, or even through a multi-room installation—can open new perspectives on storytelling and visual design. Ultimately, the timeless magnetism of three panels endures because it taps into our innate love for narrative arcs and structured creativity, inviting us to see—and perhaps create—art in a more layered and thought-provoking way.

Leave a Reply